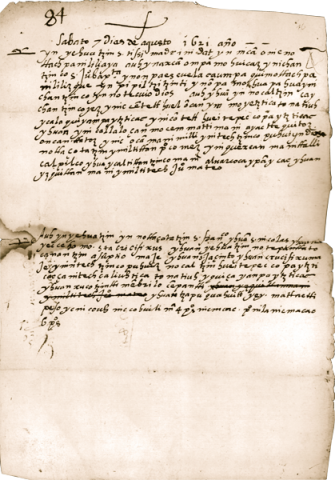

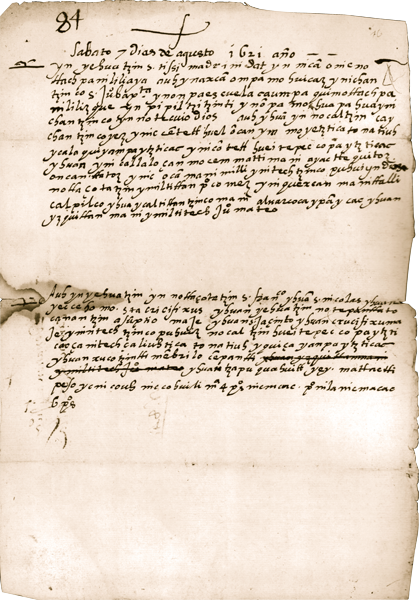

This manuscript was first published in Beyond the Codices, eds. Arthur J.O. Anderson, Frances Berdan, and James Lockhart (Los Angeles: UCLA Latin American Center, 1976), Doc. 19, 112–113. However, the transcription, translation, and a new introduction presented here come from Lockhart's personal papers.

The original is found in the McAfee Collection, UCLA Research Library, Special Collections.

[Introduction by James Lockhart:]

Puzzling and unconventional in some respects, this document at least clearly shows the cult of household saints flourishing in a large way at the beginning of the third decade of the seventeenth century.

The person who produced this text gives every indication of mastering the conventions of Nahuatl writing of the time, but after giving the date in exemplary fashion, he fails to identify either the donor or himself as notary, or the tlaxilacalli involved, and we only know that the scene is Coyoacan at all because of mention of its main church of San Juan Bautista and the fact that the text was preserved among others from greater Coyoacan.

That a donation is being made of houses and lands, and that it is of a religious nature, is beyond doubt. But the transaction seems to have been perceived differently by the donor and by the Spanish church authorities. In a notation on the back of the sheet, the latter describe it as a “donation to San Juan [meaning apparently the church of San Juan Bautista] and the cantors of this town.” (The Spanish is “donasion a St Juo y cantores desta villa.”) But taking the document on its own terms, we find that it gives the property to certain images (so we can provisionally call them) presently located at the donor’s home, above all to a representation of the Trinity that is now to be moved to the central church of the whole complex altepetl, where children of a school there are to serve it. These children must be part of the choir to whom the Spanish authorities consider the property to be partly donated.

The donor sees the images (an inextricable mixture of spiritual and material qualities, in any case far more than a representation in the simplest sense), as now being the owners of the property, a persistent motif in the Nahuas’ view of the relation between sacred objects and land. Another traditional indigenous element, well known to have reached far back into precontact times, is that attending to holy images is called sweeping for them; the donor uses that expression both for his own activity at home and for the activities soon to be taken over by the children at the church school.

In the time of the fully developed Nahua household saint cult, any word for “image” was generally notable by its absence. One spoke simply of the saints, making no distinction between saints in our usual sense and God or Jesus Christ, whose various representations also acted as saints, and indeed in this case we have an image of the Trinity as the primary saint, as well as images of Jesus among the larger group listed second.

Here we seem well on our way to the usage of the main time of the saints’ cult; the text simply speaks of the holy Trinity (also equated with “God my precious father”), of San Francisco, San Nicolás, and San Jacinto. Ecce Homo, it is true, is inherently a representation,

and so is a crucifix, though probably little distinction is made by the writer and the donor (Ecce Homo continued to appear among ordinary saints and on the same basis on into the eighteenth century).

But despite this predominant mode, a word for image does in fact appear (though in the first edition of this book it was not recognized as such). The word twice written as “maje” (lines 16, 17) is a loanword from Spanish imagen, “image.” In Spanish words that began with i or in (or even en), Nahuatl speakers would take the first syllable to be their ubiquitous particle in and thus leave it out of the corresponding loanword; syllable-final n was omitted from Nahuatl texts almost as often as not; Spanish g before e or i often appears in loanwords as j or x. Thus starting with imagen, “maje” is a reasonable written result of the borrowing process.

Actually, when a term of this type was used at all, it was usually the native word -ixiptlayo, image or representation of something in the sense of its substitute or replacement, virtually always possessed by the entity represented. Here the word “maje” is not possessed; moreover, in both cases it comes after the main designation, which in one case is “my interceding mother Asunción,” and in the other a crucifix (of which the donor seems to have two). In some Nahuatl texts one sees indications that the loanword from imagen was coming to mean not simply image but an altarpiece, a retablo, with various elements. Thus we must accept for now some uncertainty about the exact thrust of the word.

One must suspect that the donor is near death and is making dispositions of the same kind as in a will. However that may be, we do notice a distinction in the treatment of the saints. The representation of the Trinity is the sole subject of an entire paragraph, whereas seven other images are grouped together in the second; it receives a larger donation than all the rest put together, and it is said to be going (or be taken; mohuica can mean either) to the main church, whereas the same is not said of the others. We cannot be entirely sure, but it is seen at times in Nahuatl testaments that the most important saint of a family, also the most impressive as an image, is to be removed to the public church while the rest are kept at home. Among the reasons are sometimes that arguments have arisen over which relative is to be in charge of the main saint and its assets, sometimes that the authorities of the altepetl have begun to show a proprietary interest in a saint that could embellish the whole entity and its church, and at times the family too may be proud to have its own saint displayed so prominently. In any case, here the friars of the church of San Juan Bautista apparently plan to use income from the houses and lands to help support the church itself, its choir, and the school where boy choristers are educated.

The houses, two of them to belong to the Trinity and the other one to the rest of the saints, constitute a typical Nahua house complex, with separate buildings on the north, west, and east sides of a patio. The donor appears to have inherited the one on the north (often holding the senior resident) and the one on the east (facing west). It seems that he has bought the one on the west (facing east), though conceivably he has bought only the orchard that goes with it. It was common for a parent to distribute the various buildings of his/her complex to various heirs; the María and Petronilla from whom the donor made the purchase are likely his sisters. The complex has house-land, included in the donation along with two more distant plots, so that the overall structure of the holdings is as usual. Having this many saints, however, the donor is probably quite wealthy and owns other plots which he is leaving or intends to leave to various heirs. The motivation for this particular arrangement, however, may be precisely the lack of an heir in the direct line. The present document shows all the elements of the classic, full-blown Nahua household saints cult already in existence except for the typical careful allocation of the saints among the owner’s individual descendants, as in Doc. 5, dated 1695.