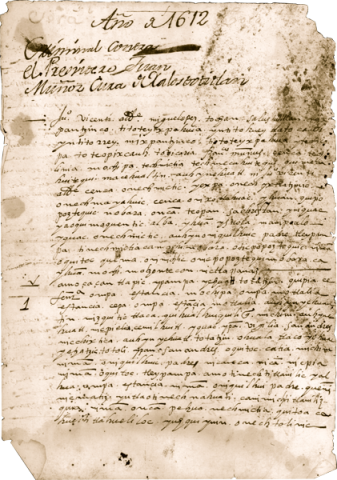

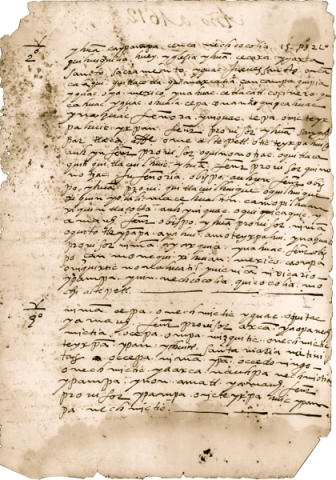

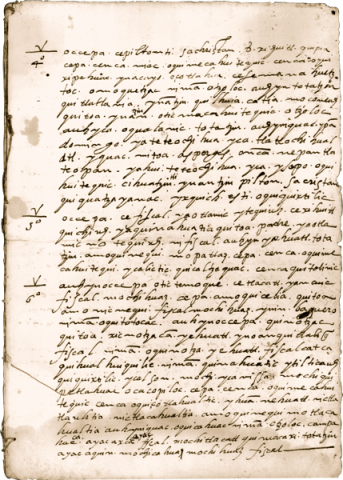

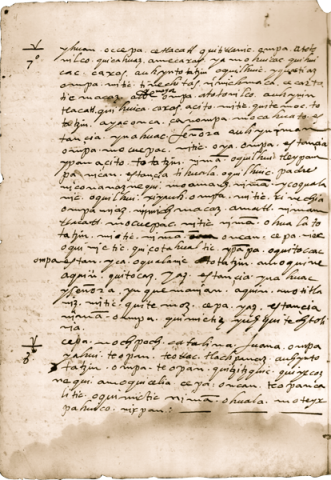

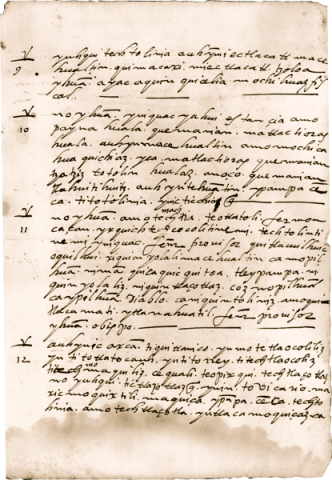

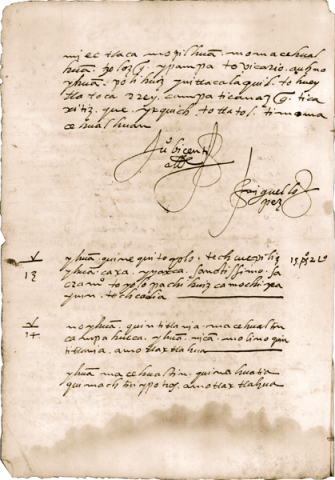

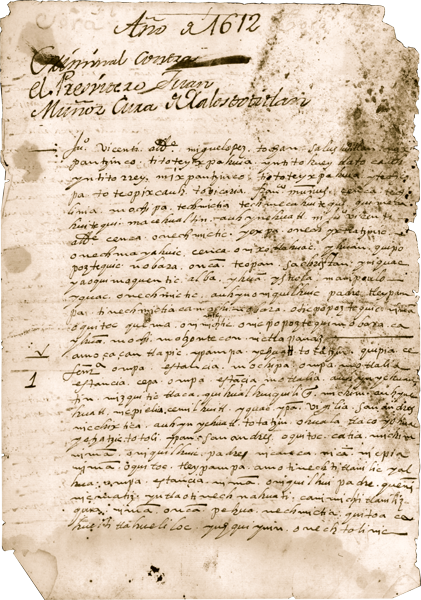

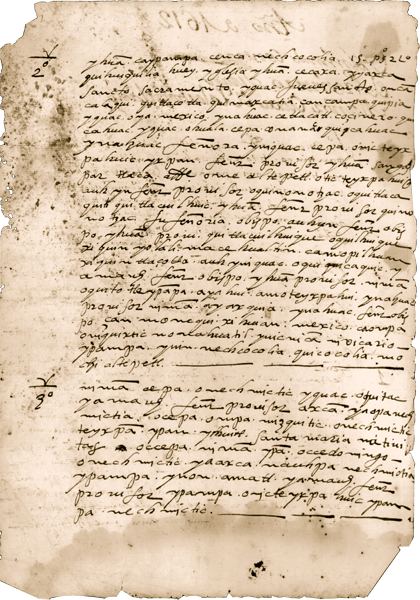

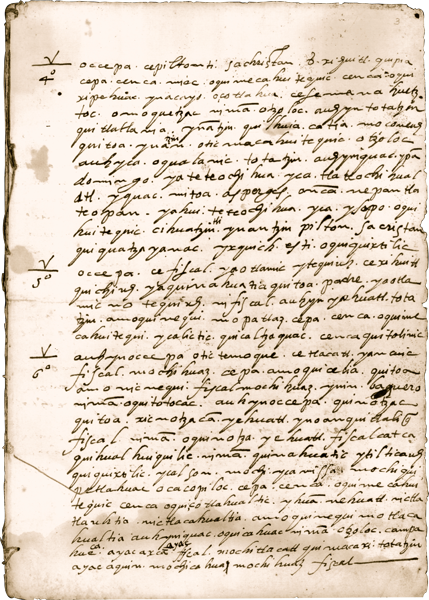

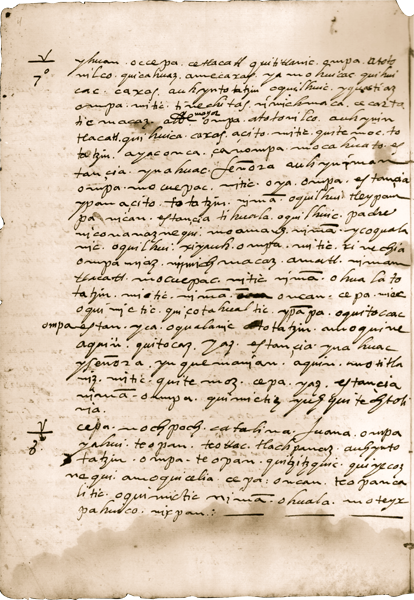

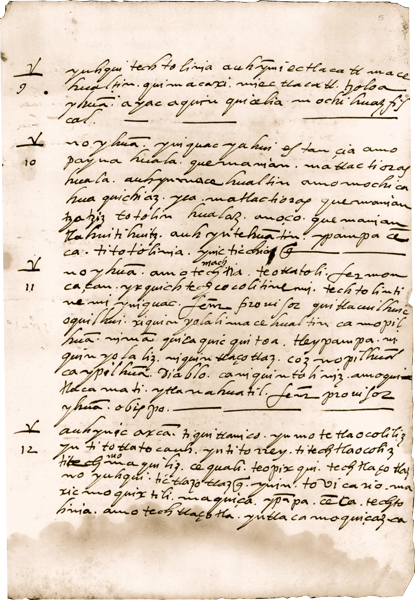

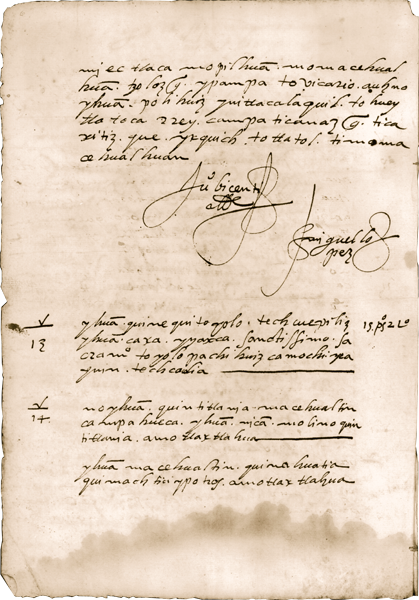

This manuscript was first published in Beyond the Codices, eds. Arthur J.O. Anderson, Frances Berdan, and James Lockhart (Los Angeles: UCLA Latin American Center, 1976), Doc. 27, 166–173. However, the transcription, translation, and a new introduction presented here come from Lockhart's personal papers.

The original manuscript is in the McAfee Collection, Special Collections, UCLA Research Library.

[Introduction by James Lockhart:]

Petitions by indigenous groups accusing the local priest of misbehavior and requesting his removal are a staple of the corpus in Nahuatl (and indeed go beyond that, existing in other indigenous languages too). Neglect of parochial duties, arbitrary and excessive beatings and whippings, sexual misconduct, undue attention to private economic activity, and excessive use of the parishioners for the priest’s private purposes are among the faults commonly alleged, often illustrated by episodes told in the most concrete detail. Without more additional context than we usually have, it is hard to judge what relation petitions of this type bear to the truth. The mere fact that such things were alleged shows that they were credible, common in real life. On the other hand, the great similarity of the complaints shows a strong element of convention, and it is clear that the authors of such texts cared much more about getting rid of the priest than about anything else.

The present text is a perfect example of the genre. It comes from Jalosotitlan, some 80 miles northeast of Guadalajara, thus in the western area and well outside the domain of standard central Nahuatl. The target of the complaint is the secular priest Francisco Muñoz, who was to get into even larger trouble with his flock some years later, in 1618.1 The complaining parties are Juan Vicente, alcalde of Jalostotitlan, and one Miguel López. Juan Vicente seems to be the real author, speaking throughout in the first person singular. The signatures of the original are in the same hand as the body; though it is entirely possible that an anonymous person did the writing, one cannot help wondering if Juan Vicente didn’t do it himself. However that may be, it is clear that the whole cabildo of Jalostotitlan was not at this time ready to support the complaint.

The document as a whole has a very homespun quality; within three or four lines of the beginning Juan Vicente is already telling episodes of the priest beating him and repeating what was said on such occasions. Only a few words of conventional rhetoric appear, concentrated in a concluding paragraph (and negated by some afterthoughts in the same vein as the body). The substance and manner of what is said are so clear that the reader will readily appreciate them from the text and translation themselves. Here let us concentrate on aspects of the language.

Originating in the western region, Jalisco, the text was not necessarily composed by a native speaker of Nahuatl. In 1612, a month after the petition was presented in Guadalajara, an investigator returned to Jalostotitlan and took testimony from five witnesses who were “fluent in Nahuatl,” (“ladino en lengua mexicana”), as though this was something not true of the whole local population. (As usual, the testimony was recorded in Spanish.) The witnesses tended to say, by the way, that Francisco Muñoz did his job and just had a very bad temper, although we cannot lightly give full credence to that any more than to the petition, for those testifying were likely of a faction opposed to Juan Vicente.

Looking at the language itself, its apparent naiveté and simplicity might reinforce a belief that it is some sort of pidgin. Yet such is not the case. A type of Nahuatl with a well defined profile existed in Jalisco and surrounding regions, and the present text conforms to it. If we attend closely, we will see that the writer has quite a large Nahuatl vocabulary and says whatever is needed with adequate words.

The petition does indeed show the usual western traits, seen also in Docs. 8, 28, and 31. The most pronounced characteristic is the manner of formation of the preterits of verbs. In western Nahuatl, Class 2 verbs, which in central Nahuatl lose the final vowel, retain it, falling together with the unreduced preterits of Class 1, whereas the verbs of Class 3, with two final vowels, lose a vowel as they do in the center.

Our text is full of verbs, and they conform fully to the pattern. And as is common in western Nahuatl, they may or may not bear the preterit marker o-, and may or may not show the preterit suffix -c.

Thus the verb poztequi, “to break something in pieces,” which in the center is a Class 2 verb with the preterit o(tla)poztec, here appears unreduced without -c (“onicpopoztequi,” “I splintered it,” line 13), with -c (“oticpopoztequic,” “you splintered it,” line 12), and also with -c but without o- (“quipoztequic,” “he broke it,” line 8). See also “quinotzac,” “he called him” (line 79) and “oquinotza,” the same (line 80). The suffix -c is included in the text much more often than not.

1John Sullivan has published the substantial Jalostotitlan material of 1618 in Ytechcopa timoteilhuia yn tobicario . . ., Pleito entre los naturales de Jalostotitlán y su sacerdote, 1618. See especially his thorough analysis in “The Jalostotitlan Petitions, 1611–18,” which both describes the language phenomena in detail and puts them in a broader context.

Despite the large number of consistently unreduced Class 2 preterits, however, it must be admitted that in one example the central Nahuatl pattern prevails, though without o-: “quichiuh,” “he did it” (line 71).

The preterits of Class 3 verbs in the document, though like the center in losing the final vowel, also mainly have the -c suffix, which is lacking in the center. Some, however, omit the -c. Thus “oquitoc,” “he said it” (line 23), but “oquito,” the same (line 43); likewise “oniquilhuic,” “I told him” (line 22), but “oniquilhui,” the same (line 24).

What the presence and absence of -c means for pronunciation is hard to say. The versions with no suffix could easily have weakened the consonant [k] to a glottal stop which was still present but not shown in writing. The Class 3 preterits present the problem that in the center the preterit ends in a glottal stop, which is part of the stem; it could not be followed by another consonant. Either the glottal stop is entirely lost, or the -c is its replacement. It is indeed possible that -c here represents the glottal stop or some other weak sound, for in line 74 we find “ycalictic,” “inside his house,” with c in the slot where a glottal stop is expected. The use of c in this position also happens in some unorthodox writing of areas closer to the center, the Toluca Valley and Tulancingo specifically.

To round out the picture with the preterits of verbs, the irregular verb yauh/huallauh, “to go/to come” follows the central pattern in the text; see “oya,” “he went” (line 33), and “ohuala,” “he came,” (line 103, and there are other examples). But the singular present of yauh is archaic, with “yahui,” “he goes,” rather than standard yauh (lines 112, 120.)

In many western texts t appears instead of tl, though never consistently. Some sort of merging was taking place; probably [t] was being pronounced instead of [tl]. In this text tl is orthodox in the great majority of cases, but some t for tl occurs: “esti,” standard eztli, “blood” (line 67), “ytilticauh,” standard itlilticauh, “his black” (line 82); “quiçotahualtic,” standard (o)quiçotlahualti, “he made him faint” (line 104); matlacti,” standard matlactli, “ten” (lines 121, 122).

Another western (and general peripheral) trait is the use of ya instead of central ye, “already.” The former occurs eight times in the text, the latter not at all.

As seen in some other texts here, the western region and perhaps much of the periphery in general used the relational word -nahuac, “close to, next to,” more than the central speech area and in different senses. Here also the word is prominent, at times functioning as it would in the center, but also in senses more peculiar to the west, as in “amoteyxpahui . ynahuac prouiSor . nima¯ . ayaxquia . ynahuac Senr— obispo,” “you complained to the vicar-general, and then you were going to go to the lord bishop” (lines 43–45), where the sense of -nahuac is virtually “to.”

A word not seen in the center but common in the Jalostotitlan corpus is paina, from a verb meaning “to hasten, run,” used as an adverb “quickly”; it occurs here in line 120.

Let it be noted that some characteristic western phenomena are missing in the text, including the present plural of verbs in -lo, seen in Doc. 28, and the retention of the absolutive ending on possessed nouns (Doc. 31). Also, the first person reflexive prefix to, a peculiar trait of the center, is used once (“titotolinia,” “we are afflicted,” line 124), and the western/peripheral mo is missing in that position. However, Sullivan has identified all these things in the larger Jalostotitlan corpus.

The question word cuix, “perhaps,” took on different forms in different regions. Here it is “coz” (line 130). The form is not peculiar to the west; a text in this collection from the Mexico City (Doc. 17) area has “cux.” (In the Jalostotitlan ç/z and x alternate, as we will see in a moment.) In both cases the rounding of the first consonant has been lost while the following vowel has been rounded.

The text shows much variation in the department of sibilants and affricates. The letter ç (normally [s]) alternates at times with x (normally [sh]); thus for “to faint” we see both çotlahua (the standard) and “xotlahua.” Alternation also occurs between ch (normally [tsh]) and tz (normally [ts]). The verb choloa, “to flee,” occurs only as “tzoloa.” On the other hand, the second person singular object prefix mitz occurs only as “mich.”

Overall, then, whether or not the present text is by a native speaker of Nahuatl, it conforms well with patterns seen in other western texts and to some extent those from the south as well.

In matters of Spanish influence, the document is full of loan nouns and some other Stage 2 traits, but has no obvious phenomena of the type associated with Stage 3 in the central area. Sullivan, however, has found two common loan particles in the 1618 documents, indicating that Stage 3 may have impinged on the periphery, or at least the west, earlier than on the center.

Throughout the text we see pia, which in the center by this time had added the meaning of Spanish tener, “to have,” to its traditional meanings centered on “to keep.” Here the verb is much as in central Mexico at the same time, sometimes meaning to have, sometimes to keep. The center was also adding meanings to create calques translating Spanish phrases using tener in extended meanings, and one of the most common of these is found in our text in “. 8 . xihuitl. quipia,” “tiene ocho años,” “he is eight years old” (line 57). Also in these years, the verb huiquilia was becoming dominant in the center in the meaning to owe money, and we find it here (line 30). In fact, in Doc. 4, done near to Mexico City in 1622, huiquilia has not yet shown itself, the older pialia still being used instead. Thus Jalostotitlan was at least abreast of central Mexico in matters of language contact phenomena, and perhaps ahead.

Several times the text uses the word macehualtin, literally “commoners (etc.),” and it is so translated here. That sense fits the context, yet the reference seems to be to the local population generally. In the center by this time, the word was becoming the main way of speaking of indigenous people as opposed to Spaniards. In fact, the Spanish translator rendered it as naturales or indios. In this way too, western and central Nahuatl were going parallel.

In line 21, “tlaco yohuac” looks as if it could mean midnight, but the usual expression for that is different, and the context demands dawn; the literal meaning seems to be “half dark.”

In line 40, “proui” is for “prouisor,” “vicar-general.”

In line 62, “oticmacahuitequic” is a slip for “oticmecahuitequic,” “you whipped him, struck him with a rope.”

In line 66, “pilton” is for “piltontli,” “little child.”

In line 87, no doubt only one of the two occurrences of ayac, “no one,” was intended.

In lines 104–05, “estan . yca” is for “estançia,” estancia, a Spanish rural enterprise, usually for livestock.

In line 105, “quine” is for “quinequi,” “he wants it.”

In line 106, “ySeno—ra” is tentatively taken to mean “his Spanish woman,” but another possibility is “y Seno—ra,” “the Spanish woman,” with y for standard in. However, this writer generally gives in the full spelling “yn.” In Nahuatl señora meant any Spanish woman and not specifically a lady; it is often seen as xinola.

In line 139, “miec tlaca,” “many people,” is probably intended as “miec tlacatl,” the usual form and the one the phrase takes elsewhere in the text.