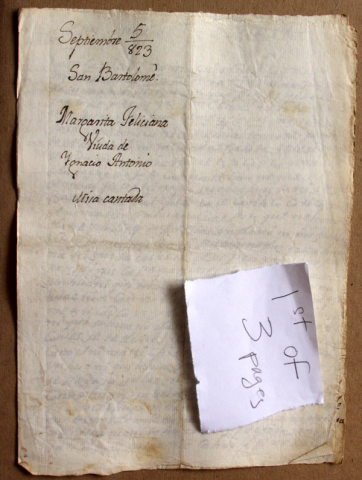

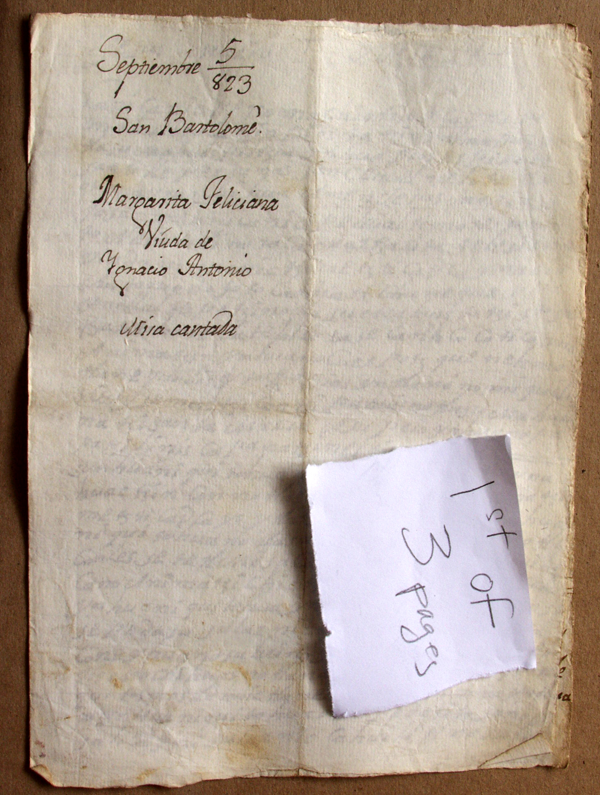

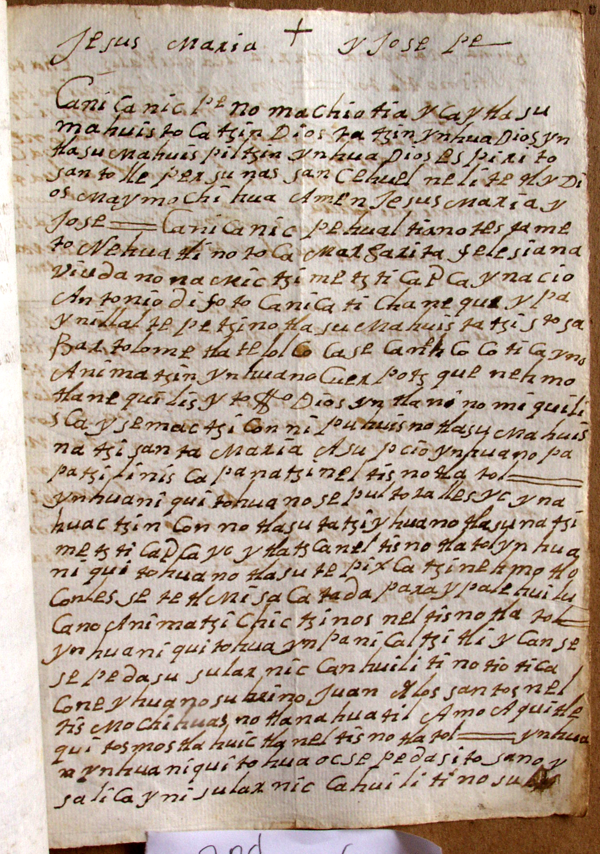

Testament of Margarita Feliciana, San Bartolomé Tlatelolco (Valley of Toluca), 1823

presented by Miriam Melton-Villanueva and Caterina Pizzigoni

THE ISSUE OF Ethnohistory for July 2008 contains an article by us entitled “Late Nahuatl Testaments from the Toluca Valley: Indigenous-Language Ethnohistory in the Mexican Independence Period.” In it we describe and analyze a corpus of early nineteenth-century Nahuatl wills from the Toluca Valley that was discovered and collected by Miriam. Their lateness, coming after large-scale production of mundane Nahuatl documentation was thought to have ceased, gives them great importance. In them the majority of testators are women, though by all indications the general position of women in the indigenous society of their time was little changed from the eighteenth century. Indeed, local society and culture held on to its general lines as well as to specific microregional characteristics even in the midst of the independence upheavals. Yet several new traits can be detected, some following earlier trends, some perhaps directly affected by phenomena of the independence era.

Since the corpus is so new, we would have liked to include with the article a full transcription and translation of one of the testaments, with detailed commentary about its idiosyncrasies and some of its implications, but that was not possible, for the journal had already allowed us a substantial number of pages. Here we present a sample testament with a full apparatus. It is referred to in the article in the hope that readers will seek it out here, and on the other hand we hope that those who come upon the present item first will also read the article, without which much of the context of the present document will remain ununderstood.

In choosing one testament we have aimed for a text as representatiae as possible. This one, like the majority, has a woman testator, is issued in San Bartolomé (in the jurisdiction of Metepec), source of the largest late Toluca Valley collection yet found, and is written by the notary responsible for the bulk of the late San Bartolomé corpus. It manifests the traits highlighted in our article. It is, however, a bit larger than normal, for most of the San Bartolomé wills fit on one page or perhaps spill over by only a line or two. Also in some more substantive aspects the text is a bit exceptional, as we will see, but we think it will serve well as a concrete illustration of the nature of the corpus.

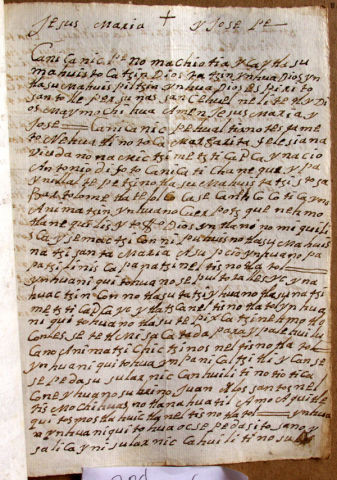

Here as in the whole corpus of Nahuatl wills from the sixteenth century forward, fully continued in the late San Bartolomé testaments, women own, inherit, and bequeath land and other property, often in large amounts, even though men are in many ways preferred. Our testator here, Margarita Feliciana, has a house on a piece of a lot (solar) and a normal amount of land for a testator of that time and place, whether male or female.

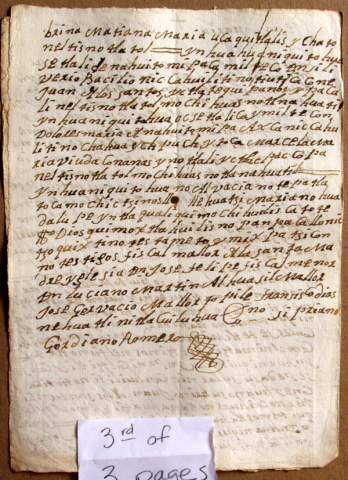

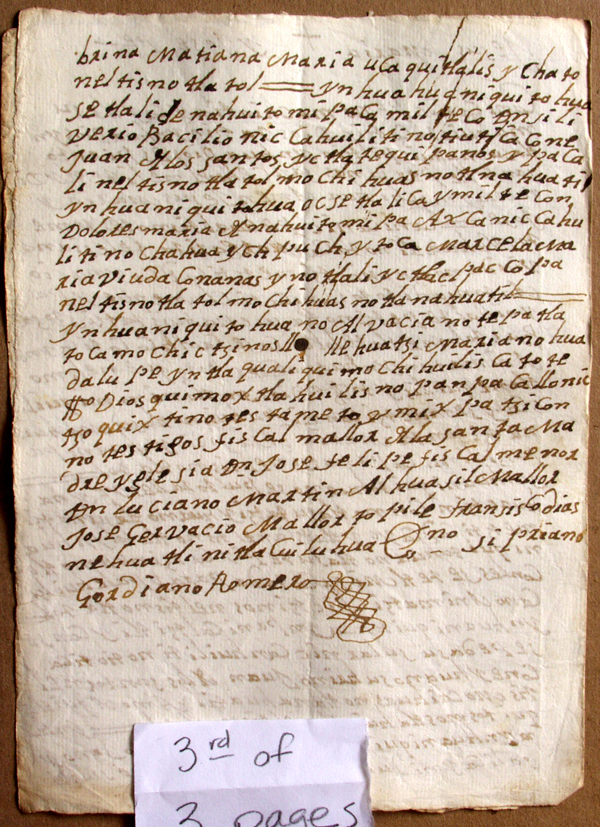

She is a widow (and indeed a majority of all female testators in this collection were widows) and has no surviving children, and so she needs surrogate heirs. Her primary heir is her nephew Juan de los Santos, whom she made her godchild in addition, strengthening the tie and making him the equivalent of her son. This duplication of kinship and ritual ties is seen several times in the San Bartolomé corpus. Note that Margarita Feliciana is careful to say that “no one is to say anything in the future,” showing that she fears someone will object to her treating a godchild as a child. Juan de los Santos receives the testator’s house and the part of her lot that it stands on, plus “4 reales’ worth” of agricultural land.

This way of measuring land by a monetary amount is new compared to the eighteenth century as far as we know, and in fact we have yet to see it in any other locality. Previously land was measured by a traditional indigenous unit, in the Toluca Valley usually the quahuitl, or in some areas it was described according to the amount of maize that could be planted in it, using the Spanish fanega and almud. Here the land is described in terms of how much income it would produce each year, given in pesos or reales (8 reales to the peso). The most common size was 4 reales, as it is here. We do not yet know what absolute dimensions are intended, though quite often a piece of 4 reales is called small. Juan de los Santos is to use the land to “serve” at the house. Possibly the meaning is to serve household saints, though that is far from certain, and saints are not so evident in the late San Bartolomé materials as in most eighteenth-century wills. In any case, the land is connected with the house, an extension forward to this late time of the traditional basic Nahua notion of callalli, “house land,” altough the term itself is lacking.

A second surrogate heir is the testator’s niece Matiana María, probably the sister of her godchild/nephew. She receives part of the house lot, though with no house on it yet, in the expectation that she will make her “little home” there. Thus the nephew is preferred over the niece, first in becoming a godchild and then in getting the house and the agricultural land.

A third heir is the testator’s stepdaughter Marcela María, herself a widow. Margarita Feliciana’s late husband had probably been married before, and the bequest to Marcela María may be more a fulfilling of duties to the hus¬band than her own inclination. In any case, the stepdaughter receives the same amount of agricul¬tural land as the godchild, 4 reales.

The testator speaks of two distinct pieces of 4 reales and gives different owners as bordering on them. Yet she also says that the stepdaughter is to take the portion that is above. In all likelihood the land has been a single quite sizable plot of 1 peso and is now being divided.

Several features of the ritual side of the testament are typical of San Bartolomé: the universal ringing of the bells, the leaving the soul in the care of the Virgin (here Asunción, the major local advocacy, though at times it was Concepción) rather than directly to God, the specific mention of the priest in connection with the mass. Even specifying the burial site as near a certain kind of tree in the churchyard was a strongly developed trait in San Bartolo-mé, though the most popular was the copal tree, not the cypress. And the majority of widows and widowers requested to be buried next to the deceased spouse, whereas Margarita Feliciana is to be buried next to her parents. It may be that her husband was buried next to his first wife.

In the eighteenth century some testators in the Toluca Valley requested a high mass, a larger number a low mass, and very few less than that. In early nineteenth-century San Bartolomé many asked for only a responsory prayer, many a low mass, and virtually no one a high mass. Margarita Feliciana is the only testator in the entire San Bartolomé corpus to have requested a high mass, and it is by no means clear why, for she was far from the wealthiest testator. In one way she fits the pattern, for in the eighteenth century men generally speaking received more elaborate religious rites and made greater offerings at death than women, whereas in late San Bartolomé the balance had shifted, and women were more likely to have masses said for them, men more likely to be satisfied with a responsory prayer.

The names in a testament are among its most revealing aspects. Here the names are overall the same as in the indigenous world of the Toluca Valley in the eighteenth century, mainly with two first names from a set repertoire, plus some religious second names like the de los Santos of the godchild/nephew, with a sprinkling of Spanish surnames. Here we have only Díaz, a humble name that had circulated among indigenous people for some generations, and the more pretentious Romero used by the notary. Some of the names, however, are of a new wave more characteristic of the late period; it would have been rare to find a man named Mariano Guadalupe in an eighteenth-century document, but by the time of independence it is common.

The honorific titles don and doña were still very meaningful in Nahuatl texts of the eighteenth century, and that is still true in the late San Bartolomé corpus. Men who held certain high municipal offices bore the don, usually for the rest of their lives, whereas lower offices did not carry the title. Here the fiscal mayor (chief church steward) and the fiscal menor both have the don, but the alguacil mayor (chief constable) and the topile mayor (topile, holder of a staff, a generalized minor officer) lack it, as does the notary even though he is an important person in the community. In the corpus in general, a majority of testators choose as executor of their will someone who bears the don, but Margarita Feliciana’s executor lacks it. And Margarita Feliciana herself lacks the doña. Since women did not hold high local office, they did not have the steady access to title that men did. Nevertheless, some of the female testators in the San Bartolomé set did have the doña. Seeing that Margarita Feliciana’s husband lacked the don and that no relatives with don are mentioned, and bringing into the equa-tion her adequate but not extensive proper¬ty, we can conclude that the testator, though in a respectable position, and even with some social ambitions as shown by the high mass, does not belong to those of the very highest rank in the community.

The testament is a typical product of Cipriano Gordiano (Romero), main Nahuatl notary of San Bartolomé in the time from 1810 to 1823, the year of this text and the last of Cipriano’s activity. It exemplifies all the normal elements of a San Bartolomé will of its time, as will be seen clearly from a comparison with the template included in our article, and in fact the bulk of these elements were already present in San Bartolomé a century earlier, as is also laid out in the article.

The document is, however, in Cipriano’s specifically late manner, which he adopted around 1816, making several of his formulas more elaborate (though not in a new vein; rather the elaborations are of a type going far back in time). Among the added items are the phrase about the Trinity being three persons but only one true God; calling San Bartolomé an altepetl and the patron saint “my precious revered father”; saying that the mass is for the help of the testator’s soul. Not least in the up-grading is the notary’s name, previously just Cipriano Gordiano, now Cipriano Gordiano Romero. Actually, his father, who had preceded him as a notary, had already consistently used Romero, a good-sounding Spanish surname, but Cipriano waited until he was very well established before laying claim to it. As we see here, he never did style himself don, though his father before him had signed his wills as don Francisco Nicolás Romero.

All in all Cipriano’s orthography and his conventions are normal for his time and place and would hardly stand out for San Bartolomé even a century earlier. But he is unusual when it comes to the preamble formula speaking of body and soul. Ever since the sixteenth century, following patterns in Spanish wills, the preambles of Nahuatl wills included a statement that the testator’s body was sick but his or her soul was healthy. Cipriano sometimes gave the formula as tradition dictated, but more often, over his whole career, he got it mixed up. His formulation here is of that type; it can be interpreted in two ways, but both go squarely against the traditional sound soul and sick body. However, in saying cuerpo instead of using traditional Nahuatl expressions for the body, Cipriano is representative of the whole late San Bartolomé tradition.

The date of the present testament is known only through what is given on the cover page, filled out in Metepec by a Spanish official (apparently the parish priest). Usually Cipriano completed the testament while the sick testator was still alive, then put the date in an additional last line done after the testator’s death. Then, often after some days, he took the testament to Metepec, where the Spanish official composed a cover page with that day’s date, the name of the testator and his or her spouse, and the type of rite to be performed. September 5, 1823, the date given on the cover page here, may not be the actual date of composition of the will or of Margarita Feliciana’s death, but it is probably no more than a week or two later.

Cipriano Gordiano’s orthography falls within the general patterns of eighteenth-century Toluca Valley Nahuatl writing as explained in Caterina’s Testaments of Toluca. Here we see a good deal of ll for standard y (as in “llehuatzi” for standard yehuatzin, line 52). Many standard n’s are missing, and many are present that are absent from standard forms.

A feature of Toluca Valley Nahuatl writing is the “Tolucan i,” a nonstandard i added after a consonant to avoid its being dropped. The phenomenon is seen in this text in “nehuatli” (lines 15, 59, standard nehuatl), which is Cipriano Gordiano’s usual form, and “siliverio” (line 40, standard Silverio).

In lines 16 and 26 we find the form “metztiCaPCa”, standard moyetzticatca. “Metzticatca” was a common variant in the Toluca Valley, but the use of p instead of t was rare or unique. It seems to have happened because both [p] and [t] were uncommon and likely to be weakened in syllable-final position.

In line 11, “tatzin” lacks a syllable; the notary would normally have written “totatzin.”

In line 13, “tetl” would normally be “teotl.”

In line 20, “noCuerpotz” lacks “i” or “in” at the end.

The normal abbreviation for totecuiyo, “our Lord,” was toteo, tteo, or above all tto. In line 21 we see “totto.” The notary forgot that the last part already indicated the whole word and added another to-, “our.”

On line 27, “notlasutepixCatzi” would normally be “notlasuteopixCatzi.”

On line 28, “nehmotloConles” would nor-mally be “nehmotloConlis.” The standard form is nechmotlaocoliliz. The a is missing from the verb tlaocolia in all known late San Bartolomé texts, apparently reflecting local pronunciation.

On line 29, “chictzinos” has lost a syllable from “mochictzinos” as in line 52 (standard mochiuhtzinoz).

On line 38, the intention of “ynhuahua” is “ynhua,” standard ihuan.

On line 39, the intention of “milteCo” is “ymilteCo,” standard imiltenco.

On line 43, the intention of “notlnahuatil” is “notlanahuatil.”

The reader will see, then, that like many Nahua notaries, Cipriano Gordiano was very prone to the omission of syllables, and some-times to their duplication.