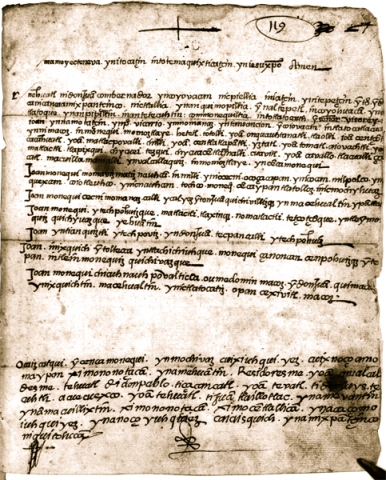

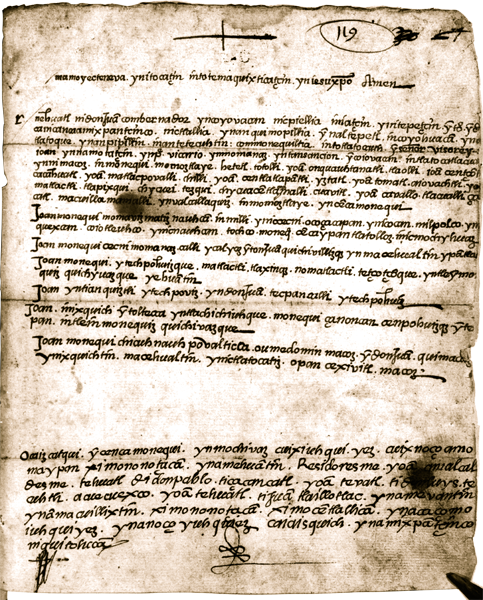

These manuscripts were first published in Beyond the Codices, eds. Arthur J.O. Anderson, Frances Berdan, and James Lockhart (Los Angeles: UCLA Latin American Center, 1976), Doc. 26, 150–165 However, the transcription, translation, and a new introduction presented here come from Lockhart's personal papers.

The original documents are in AGN Tierras 1735, exp. 2.

[Introduction by James Lockhart:]

Here are assembled a group of texts going far to define the position of don Juan de Guzmán, tlatoani and governor of Coyoacan, in the mid-sixteenth century. They belong to the larger set of material concerning the Coyoacan municipality around that time that is especially valuable in not yet having adopted Spanish genres and concepts as fully as later. Like much of that body, these texts are undated and mention no writer or notary. We see don Juan still receiving many of the services and tributes of a preconquest tlatoani, still maintaining a palace-like establishment, still holding large and widely scattered lands with many dependents on them.

The seven sections presented here are related, but are individual pieces, not in any certain order, and probably not from the same year. Section 1 may be older than the rest, dating from some time in the 1540s; the rest are surely from before the death of the first don Juan in 1569 and probably considerably earlier than that. Sections 2 and 3 are closely associated, as are sections 5 and 6.

In Section 1, lines 1–43, don Juan, claiming the backing of the viceroy and the Dominicans, asks the Coyoacan cabildo to confirm a detailed list of supplies, services, and tributes to be given him. They include a large amount of indigenous food for his large establishment; the working of four fields for him; the building of a new house; the services of carpenters and stonemasons; rights to the marketplace (which he taxes, as we see in Doc. 25); and a tax in money from the general population, to be paid twice a year. The only thing that is not purely indigenous and precontact about all these demands is the use of money a request for horse fodder.

This part is reminiscent of Doc. 18, the donation of land to the church singers, in that among the cabildo members present are don Pablo Çacancatl and don Luis Cortés. The latter as in several of the earliest texts is still referred to without the second name, simply as the lord of Acuecuexco. Given that don Pablo died in 1549, this text like Doc. 18 must be from that year or earlier (see there for more on don Pablo). The consistent use of tç instead of tz is also an early trait. So is the way that the cabildo members are addressed as if in conversation; throughout it is as though don Juan were actually saying these words in their presence, observing all the niceties. At first his audience is called only rulers, nobles, and lords, “yn antlatoque yn anpipiltin in antetecuhtin,” though later their positions as alcaldes and regidores are mentioned.

The words “tecpancalli” (line 27) and “tecpan” (line 30) are translated here as “palace.” Let it be understood that the reference is not to the building but to the ruler’s household or headquarters organization in general, as one would use throne or crown. Tecpan can readily mean either the building or the organization; tecpancalli literally speaks of the building, but cannot be intended in that sense here.

At the end of this section it is not a mistake that don Juan addresses three people by name and then says “all five of you”; two regidores must have remained unmentioned.

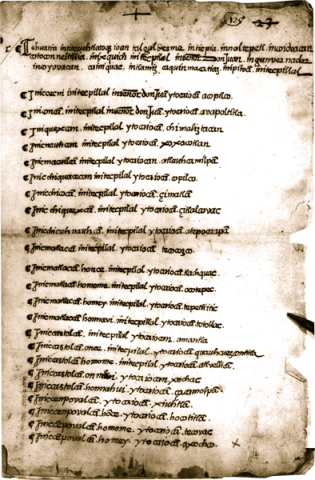

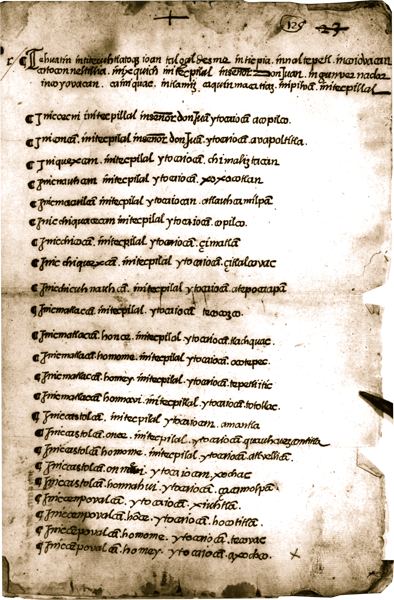

Section 2 (lines 45–72) is simply a list, in a way not in any particular genre, but it can be thought of as modeled on a Spanish memorandum, and so can all the following sections here. Indeed, Section 4 is specifically labeled a memoria. The list in Section 2 names dependents of don Juan as tlatoani; they are as scattered as his lands. Many in fact are located at places where he holds land seen in other listings, and if the lists were exhaustive and consistent we would probably find that that those listed are all on don Juan’s land.

No overall term for the dependents appears here. The one special term at the beginning, “tepantlaca” (line 46), seems to apply only to those who “belong to” don Juan and are no doubt located at the tecpan. That this word distinguishes them from the rest and is not something applying to the whole group is seen by its reappearance in the following list (line 78) among other groups of dependents from various places. One would have expected tecpantlaca, palace people. Since tepan is used here to mean “over people,” supervising them, that might seem a possibility, but in line 78 they seem to be carrying out the same tasks as others.

The list counts tlacatl, a word which means a person of either gender and is often used, as it is here, simply as a counter for human beings of any kind, and thus its translation here is “people.” Nevertheless, since those who are simply unqualified “people” are differentiated from mere youths (“telpopochtotonti[n],” lines 55, 59, 68) and from widows, they must be adult men. The total given is 380 plus widows; this is correct, consisting of 366 adult men and 14 youths. There are 21 groups of them, varying in number from 2 to 80.

Section 3 (lines 74–95) is a list specifying duties of some of the same dependents who figure in Section 2. Their tasks seem mainly traditional, clearing the ground and cultivating it, but in one case they are reaping the Spanish crop wheat, and in another they are working with oxen. They are also providing lumber to a Spaniard. Groups at a given place work as a unit, and in several cases supervisors are mentioned, who all have indigenous second names (for one only a first name is given), so they are not of the highest rank. One of them (line 83) is called by the indigenous name only, an archaic trait.

In this listing we finally get some terms that describe the dependents in general. The first, with the most clearly general intention, is -macehualhuan, the possessed form of macehualli, in “in imaceualoan señor don juan” (line 75). Unpossessed macehualli means ordinary person, person of low rank, commoner, but by our general understanding the possessed form means someone’s subject or vassal regardless of rank; a great lord could be the -macehual, subject, of a tlatoani. For that reason the translation here of the words just quoted is “the vassals of lord don Juan.” But quite possibly in this case the status implication of the term is retained even though possessed, so that the words could mean “the macehualtin of lord don Juan,” and macehualli would be the blanket term for the dependents, no different than with the general commoner population. The question must be considered unresolved for now.

Another term used for the dependents in this section is temiltique (line 86), meaning those who provide cultivated fields to someone, i.e., work them for someone else. “Field workers” is an adequate translation. The word is used again in lines 291, 304, 315.

Among those with assignments are “in tlachichiuhque ioan tlapanauique” (line 89). Tlachichiuhque means literally “those who fix things up” and can be reasonably taken to be artisans. Tlapanahuique are literally “those who exceed, go beyond, excel.” Possibly the reference is to people who for various reasons are raised above the group as a whole. Neither term is known in this connection from other texts, so we remain in considerable uncertainty. At any rate, these people are not said to be at any one location like the other groups and may be scattered about. Their tasks are likewise dispersed, to work don Juan’s greatly scattered purchased land, which we will later see was mainly in smaller parcels than his other holdings.

A large problem in this section is a repeated expression chicomilhuitl, “seven days,” in connection with the groups’ work assignments. In most cases it lacks the ordinal ic or inic, so that it should be durative, for seven days. In the first entry, lines 75–80, although the placement of the word in the paragraph is rather odd, we get a satisfactory sense, that a series of groups will clear ground in San Agustín, taking turns of seven days each.

In other instances, seven days is mentioned in connection with a single group. One is left wondering if the whole group is to work only seven days, or if individuals in it are to take seven-day turns, keeping the activity going. In one case the expression used is “inic chicomilhuitl,” which should normally be “the seventh day,” leaving the meaning unclear.

Section 4 (lines 97–198), specifically called a memorandum, is the first of the three land lists in the present set, by far the largest, and the only one to give measurements for the parcels. First come the inherited lands of the ruler’s household, as we can fairly deduce even though only a few are called huehuetlalli, “old land,” land associated with long enough to be identified with it (lines 107, 109, 117). Here the word is translated as “ancestral land”; “patrimonial land” would have done as well. Though the estate is much more extensive than that of an ordinary person, its structure is the same: callalli, “house-land,” land with the residence on it, listed first here (although the houses in this case are a palace and a huehuecalli, “ancestral house”), followed by scattered distant land. When the lists are seen as a whole, don Juan’s holdings are seen to stretch over all four of the basic sub-altepetl of Coyoacan in addition to the more recent fifth, San Agustín Palpan, as is demonstrated in the extensive compilations concerning don Juan’s land in Horn, Postconquest Coyoacan, pp. 256–57, where much more can be learned. (Follow the index entries “land, Nahua,” and “Guzmán, don Juan de.”)

The list starts out to be organized by Acohuic, the upper region, and Tlalnahuac, the lower region, so basic to the structure of the altepetl of Coyoacan. At the beginning it is announced that don Juan’s Acohuic land will now be listed; but no parallel list for Tlalnahuac then appears. Apparently the writer simply forgot to indicate the division. Atlhuelican and Xochac (lines 112–19) were in Tlalnahuac (Horn, ibid.), and it certainly seems that the following Chinampan, “where the chinampas are,” would have been too.

The inherited lands are substantial but not as numerous as one would have thought, not are they all huge. The other listings imply that this is not all of them.

Next comes a list of don Juan’s purchased lands, tlalcohualli (line 132), this time consistently divided between Acohuic and Tlalnahuac; that is, the Tlalnahuac part coming first is not labeled, but the following Acohuic part is and makes the distinction clear. It is notable that there are many, many more such holdings in Tlalnahuac than in Acohuic. With a few exceptions the purchased parcels are not large, the smallest being 5 quahuitl long, 1 quahuitl and a fraction wide (line 191). This is not the place to speculate what such holdings meant for the manner of operation of don Juan’s estate.

This list and Section 7 are the only parts of the present set to include precise land measurements. Both use the quahuitl, the most common unit across the Nahua world. The one employed in Section 7 (line 292) is said to be of twelve feet, matlactlacxitl omome. That was not necessarily the same in the other case, however. The quahuitl used in the land investigation in Doc. 9, also in the Coyoacan region, was of ten feet. Both ten and twelve feet are larger than what is generally considered the normal size range for the quahuitl, but we do know it varied, and not knowing the precise size of the “foot,” little precision can be attained.

The measurement in Section 3 is so careful that it gives fractions of the quahuitl when applicable. The fraction most employed here is the matl, which in many places was simply the word used locally instead of quahuitl and meaning the same thing, or sometimes alternating with it. Here it is clearly something less than the quahuitl. One might hazard two-thirds, but there is nothing definite to go on. Once (line 165) the fraction specified is the yollotli, “heart,” often defined as the distance from the middle of the chest to the the end of the fingers with arm outstreched.

Sections 5 and 6 make a pair, simply listing lands of don Juan’s with no measurements. The three land lists do not closely agree as to the items included, though there is indeed some overlap. Part of the explanation may be that different names were used for the same plot at different times, for these are not actual names of the parcels, but the names of places where they were, and many places were bits and subdivisions of others, so that a given plot could be in two or three of them at the same time.

Section 5 (lines 199–239) lists the lands to which don Juan at some time was given formal possession, using the Spanish loanword for the act; it was apparently sanctioned by Spanish officials (in a separate procedure), and the document speaks of the king giving the lands to don Juan.

Again we see the structure of house-land vs. distant land, this time fully explicit, for the list begins with the very word, callalli (line 202), which also occurs again three lines below.

Two orchards are mentioned (lines 206, 208), something the ruling lineage was famous for owning. Note that although in some other texts from Coyoacan (Docs. 2, 4) the word appears simply as huerta, here we see the classic form alahuerta.

The list is divided into Acohuic and Tlalnahuac, and this time Acohuic has more items, 21 to 11.

In Section 6 (lines 241–89) the alcaldes of the cabildo confirm don Juan’s rights to a series of landholdings as his tecpillalli with the right to hand it on to his children when he dies. Teuctli is lord, pilli is nobleman, so tecpilli is lordly nobleman. Hence tecpillalli is translated here as lordly nobleman’s land. It belongs to a long series of precontact land categories for the holdings of rulers, lords, and nobles. Most are ill reported in Spanish chronicles and poorly understood to this day. It is at least interesting that the term is still being used here. The meaning of such words is best defined by their use in texts; here we have a good concrete example.

This list is not openly divided into Acohuic and Tlalnahuac, but it seems that the last portion, beginning with Amantlan (line 275), is Tlalnahuac (see Horn, ibid., and lines 224–36 just above).

Section 7 (lines 289–317) demonstrates a change that is going on in the traditional system. Dependents on the ruler’s lands are beginning to take them over for themselves without getting permission. We saw the same thing with the lands of the Tlaxcalan teuctli don Julián de la Rosa in his 1566 will (Doc. 1). Don Juan’s reaction seems the same as don Julián’s, partly acquiescing in the inevitable and giving away some lands to the occupants, partly opposing. Here the alienation of ruler’s lands both voluntary and involuntary is massive. Some of these pieces are larger than anything mentioned among don Juan’s holdings, the largest being a huge 500 quahuitl by 40, enough for fifty standard 20 by 20 plots. We apparently see here the reason why don Juan’s parcels are not presently larger, and perhaps also the reason for so much purchased lands in small bits.

As mentioned above, the term used here for the resident dependents or former dependents is temiltique (lines 291, 304, 315); twice it occurs in the possessed form, don Juan being the possessor.