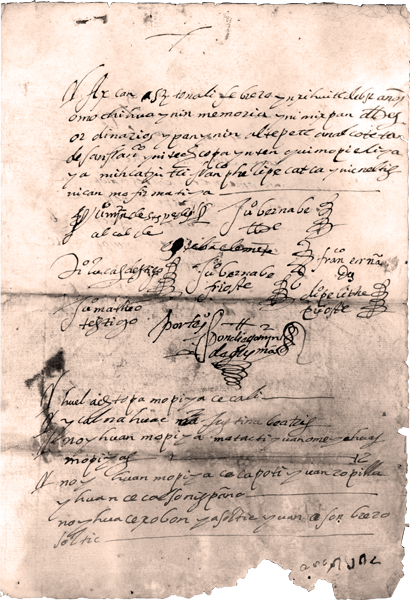

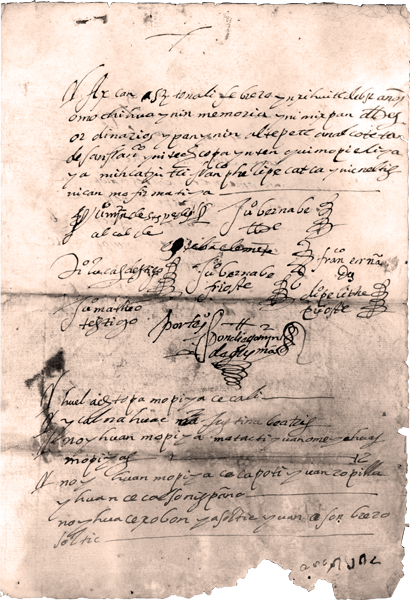

This manuscript was first published in Beyond the Codices, eds. Arthur J.O. Anderson, Frances Berdan, and James Lockhart (Los Angeles: UCLA Latin American Center, 1976), Doc. 8, 78–83. However, the transcription, translation, and a new introduction presented here come from Lockhart's personal papers.

The original is found in the McAfee Collection, UCLA Research Library, Special Collections.

[Introduction by James Lockhart:]

To date Analcotitlan has not been located, but the text seems to belong with the considerable body of materials in the McAfee Collection that come from western Mexico, and its language has some of the characteristics of that region, as will be seen in more detail below.

Municipal and cofradía officials are in charge of the proceedings. In addition to making an inventory of the assets of Francisco Felipe, the steps taken include organizing and paying for funeral observances for him, but the emphasis and primary motivation have to do with collecting his debts to the cofradía and the altepetl. He was likely the mayordomo of the cofradía, which involved acting as treasurer, and he has ended up with a hefty debt to the organization.

The two outstanding features of Francisco Felipe’s property as listed are first, some fancy, up-to-date clothing in Spanish style (though much of it naturally showing signs of wear), and second, evidence of his being a horse breeder on quite a large scale. He owned no fewer than twelve brood mares and had an impressive set of farrier’s or blacksmith’s tools. On the other hand, we hear nothing of landholdings.

With the debt to the cofradía, the peso amount is given as “15 . 1,” with 2 reales in addition (line 30). Here the writer, although using Arabic numbers, is reckoning by the traditional Nahuatl system in which 16 is 15 + 1, caxtolli once. Thus the Spanish annotation in another hand, “deue 17 pos 2,” is a correction adding a peso to the total.

In many ways the language of the text is a quite normal Nahuatl, but there are numerous signs pointing to the western region, traits often shared with Doc. 27 from Jalostotitlan.

The preterits of verbs are different than in central Mexican Nahuatl, and in exactly the same way as in Doc. 27. The only preterits which are orthodox are the plurals, as well as the singulars of unreduced Class 1 verbs, thus “omonamacac,” “it was sold,” in line 59. All the singular preterits of Class 2 and 3 verbs are unorthodox by the standards of the center. Central Nahuatl Class 2 verbs drop the final vowel in the preterit; here they retain the final vowel and may or may not have a suffix. Thus mochihua, “it is done,” appears in the preterit as “omochihua” (line 49) and “omochihuac” (line 54), but not as omochiuh, the central form. The version with no suffix may be explained by the weakening of the final [k] in speech to the point where it was sometimes not perceived. The single example of a preterit Class 3 verb in the singular, “oquitlaneuhtic,” “he borrowed it” (lines 34–35), again varies from the central form, which would be oquitlaneuhti. The preterit loses the a of the present tense in both versions, but the form here has -c instead of the unwritten glottal stop of the center. To repeat, all these traits are equally illustrated in the document from Jalostotitlan.

Also as there, we see switching back and forth between t and tl, above all in the absolutive ending (“tepostli,” “metal,” line 23; “teposti,” line 25), but also elsewhere (for Analcotitlan, in line 3 “analcotetan,” in line 37 “analcotetlan”).

And again as in Jalostotitlan, the relational word -nahuac, “close to, next to,” is used more broadly than in central Mexican Nahuatl. Twice it appears in connection with owing money to someone, indicating the indirect object in a way it did not do in the center, as in “quitehuiquilia ynahuac Juo matheo,” “he owes it to Juan Mateo” (line 34). But the same expression also occurs in the central style, without -nahuac: “altepetl quihuiquiliya,” “he owes it to the altepetl” (l. 33).

Thus in several ways the document shows typical western language traits, but accompanied by signs of central Nahuatl influence of some kind as well.

The text was composed around the outset of Stage 3 as manifested in central Mexican Nahuatl, but even in the small sample here we see that Analcotitlan is keeping up with the center in language contact phenomena and orthography. Indeed, more generally one tends to find the peripheral areas up to date with or even moving more quickly than the central region. The most important orthographic innovation of Stage 3, the replacement of c/z by s, has become the norm here, though there are some exceptions and indeed one hypercorrection in the other direction, “çacramēto” with ç where there had already been an s.

No loan verbs occur in this brief text, but the loan particle sin, “without,” is seen twice (lines 27, 28). In “medias verdes” (line 18), “green hose,” “raso asul” (line 19), “blue satin,” and “ligas asules” (line 20), “blue garters,” we see Spanish adjectives as loanwords. The borrowing of adjectives was always rare and is associated mainly with Stage 3, but the color words began to come in somewhat earlier, and usually as here in direct connection with loan nouns, as though the two words were a single substantive expression.

The native verb huiquilia, which in central Mexico first came to mean to owe money in the second and third decades of the seventeenth century, is already standard in that meaning in the present text. In line 27 “yca,” standard ica, an instrumental relational word, is used as the equivalent of Spanish con, “with,” just as was happening in the center. The text also contains a plethora of loanwords for technical and rare items, but Nahuatl had already begun to do that far back in Stage 2.

Twice (lines 3, 37) the name of Analcotitlan is written with e instead of i (”analcotetan,” “analcotetlan”). However, replacement of i by e is not seen anywhere else in the text. [Note from Stephanie Wood: There was a corregimiento of Analcotetlan in the Tonalá region of the larger region of Guadalajara, Nueva Galicia.]

In lines 18 and 21 “soltic,” “used, old, worn,” has lost a syllable from standard içoltic, but in line 58 the first syllable returns in “isolti” (though the final c disappears).

In line 21, “palona” is from Spanish valona, a type of large soft collar, in line with the frequent substitution of p for Spanish b/v. Most loanwords in the text, however, are reasonably close in spelling to the Spanish originals.

In line 36, “tlatuque,” standard tlatoque, “rulers,” is used for the officers of the cabildo and other prominent men in the same fashion as it long had been in central Mexico.

In line 40 and elsewhere, don Diego Martín de Guzmán is the only person other than the notary who actually signed his own name. Also the title don and his noble surname raise him above anyone else mentioned, though the alcalde Céspedes has a very good-sounding surname too.

In line 42 the somewhat archaic native term amatlacuilo, “writer on paper,” is used instead of the loanword escribano for notary. The i of the first person prefix is not elided as it would be in the center: here “niamatlacuilo,” standard namatlacuilo.

In line 49, the standard form of “huencintli,” “offering,” is huentzintli. Perhaps here [ts] has been lenited to [s].

In lines 55–56, in “monamacatiyahu,” “-tiyahu” would standardly be written -tiyauh or tiauh and is the equivalent of -tiuh, the progressive auxiliary based on yauh, “to go,” so that the form means “it goes along being sold.”