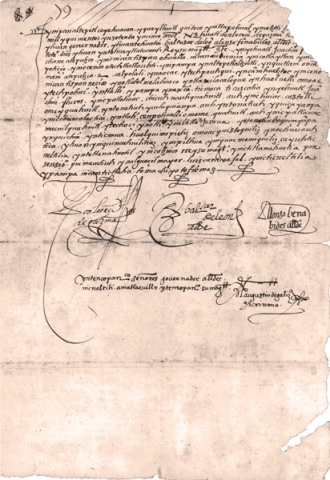

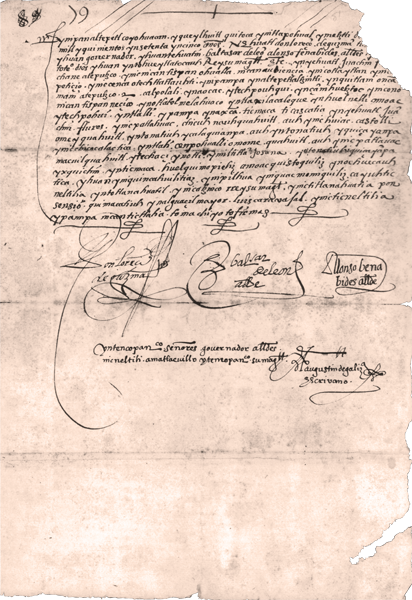

This manuscript was first published in Beyond the Codices, eds. Arthur J.O. Anderson, Frances Berdan, and James Lockhart (Los Angeles: UCLA Latin American Center, 1976), Doc. 13, 94–95. However, the transcription, translation, and a new introduction presented here come from Lockhart's personal papers.

The original is found in the McAfee Collection, UCLA Research Library, Special Collections.

[Introduction by James Lockhart:]

Formal written grants of land inside indigenous entities are known across the postconquest centuries, but they are not very common. The present example is quite like a Spanish grant of the simpler kind, but the joint action of the unnamed group of citizens and/or authorities of the tlaxilacalli affected is more typical of indigenous procedures.

The land in question is a piece of irregular shape amounting to less than half of the standard size of 20 units square, located in the grantee’s home tlaxilacalli. The grant is justified by the fact that the plot is presently unoccupied, as the local people testify. Note that the terms altepetlalli, “altepetl land,” and calpollalli, “calpolli land,” both apply to the same piece (as Charles Gibson long ago presumed that they would). We see here also that although tlaxilacalli is the greatly dom¬inant term in Nahuatl records of postcontact times for constituent parts of an altepetl, calpolli as here is often preserved in frozen compounds.

No particulars are given here about the recipient of the grant, Joaquín Flores of Atepotzco. Elsewhere in the McAfee Collection is the 1602 testament of don Joaquín Flores of the same place, Atepotzco, described as in Santo Domingo Mixcoac, one of the subaltepetl of Coyoacan. His properties are not closely specified, but he had held high office and been responsible for the payment of tribute, and the notary calls him tlatoani, with some implication that he was a hereditary lord or ruler. Possibly this is the same person, who, as he rose in life and usage became more generous over time, acquired the don and high municipal position. Just as possible is that the testator of 1602 was the son of the grantee of 1575. Either way, it is clear that the grant went to a person of local prominence and that formal grants like this would not have been handed out to just anyone in the Coyoacan of that time.

In line 5, note the reversal of b and v in “fenabides” for Benavides and the substitution of f for v, all expectable phenomena in that none of the sounds these letters represent existed in Nahuatl before contact.

In line 11, “ça¯nihuetztoc” = çaniuh huetztoc, “it lies just as it is,” unimproved, fallow or unused.

In line 12, the word tlaxilacaleque can equally well mean inhabitants of the tlaxilacalli or tlaxilacalli leaders; in contexts like this one, we expect the meaning to be the district heads, but the other possibility still exists.

In lines 29–30 we see the indigenous term amatlacuilo, “writer on paper, notary,” as well as the loanword escribano. The latter quickly and generally displaced the former, but the native term still surfaces at times in texts of Stage 2, and in several Coyoacan items here from around this time.