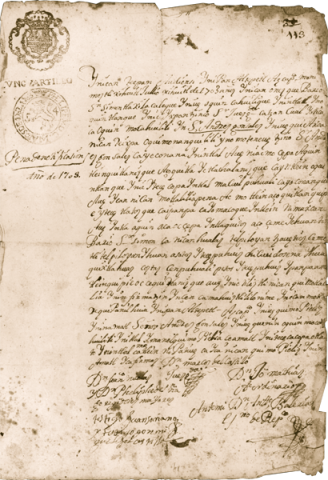

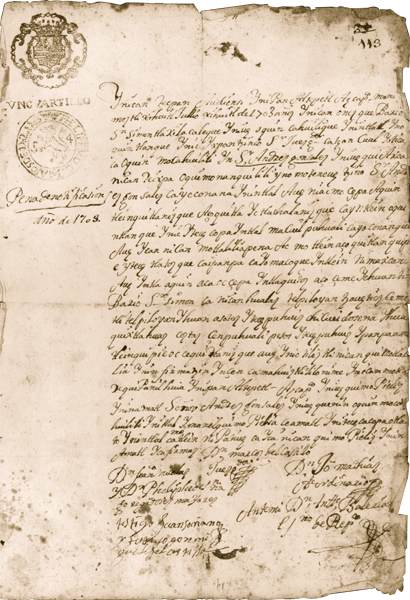

This manuscript was first published in Beyond the Codices, eds. Arthur J.O. Anderson, Frances Berdan, and James Lockhart (Los Angeles: UCLA Latin American Center, 1976), Doc. 14, 96–97. However, the transcription, translation, and a new introduction presented here come from Lockhart's personal papers.

The original is found in the McAfee Collection, UCLA Research Library, Special Collections.

[Introduction by James Lockhart:]

By 1700 or before the municipal organizations of many central Mexican altepetl, especially larger ones, had absorbed so much of the concepts and procedures of Spanish law that they were producing legal documents in all the same genres the Spaniards used, arranging the elements in exactly the same order, with close equivalents of the Spanish formulas and other vocabulary. The present text is of this type.* But such texts usually retained many traces of traditional Nahua traits, and they were not always as well informed about things Spanish as they seem to be. The example here is in the Spanish genre of a notification of penalties, and the phrase in Spanish is actually used as a label for the text. However, it is backwards, speaking of a penalty of notification.

The situation is that the Spaniard Andrés González has been disputing over certain lands with the inhabitants of the district of San Simón (Pochtlan), the same entity where Doc. 5, the 1695 testament of Angelina, was issued. He now concedes that a large piece of 100 quahuitl belongs to the indigenous people, but the main thrust of the document is that they are to make no further claims about the land that has been in dispute, and heavy, indeed probably rather unrealistic penalties are set as a deterrent against any of them trying to reopen the matter.

Andrés González (without “don” and probably a pretty humble person in the Spanish world) is not specifically termed a Spaniard, but that is conveyed in this context by his being called “señor.” The family is gradually accumulating land in the San Simón district; Andrés is the father of the land purchaser in Doc. 17, also concerning San Simón, issued in 1738.

A typical traditional feature of the proceedings here is the important role of an anonymous group of district inhabitants. Though San Simón is referred to in the Nahuatl as a barrio (line 3), the attending group is called tlaxilacaleque (line 4), based on the traditional term tlaxilacalli, constituent district of an altepetl. Very likely the group consisted entirely or mainly of officials or leaders of the district, for “tlaxilacaleque” meant both inhabitants and leaders of the entity.

This is Stage 3 Nahuatl, but there is little occasion for anything specific to that stage to appear here. In line 9 the strange form “niacmo” may contain the popular loan particle ni, “nor,” thus being the equivalent of ni aocmo and meaning “nor any longer.” The o of aocmo, “no longer,” is omitted in other places in the text as well. A fuller demonstration of the contact phenomena of the time is seen in Doc. 17 and is discussed there.

One of the main signs of Stage 3 orthography is that z becomes s. Here, despite the date, that has not yet quite happened. Syllable-final [s] is still mainly written z. But the merging of s and z as [s] has indeed taken place, as we can tell from the fact that standard s is usually hypercorrected to z, for example in “coztaz” (line 17) for costas, “costs.” In line 18 s and z are inverted, “asotez” for azotes, “lashes.”

As Stage 3 proceeds, we see ever more of an extra y added to the beginning of preterit verbs, as here in line 11, “yoconanque,” “they took it,” and line 13, “Yomacoque,” “they were given it.” Perhaps the y is from ye, “already,” and still has something of that meaning. Most preterits here have only the standard o-.

In line 2, the word tecpan, which originally meant the palace of the lord or ruler of an entity, now means its government building, and the change is not great, since the palaces had public functions and in a sense belonged to the whole entity. The form “Audensi” for audiencia, “court in session,” is quite often seen; Nahuas tended to omit the second of any two final vowels in a Spanish loan noun.

In line 16, “tzauhtiyez” is the equivalent of tzauctiyez, “will be enclosed.”

In line 19, a syllable was inadvertently omitted: the intention of “tiliztli” is “neltiliztli.”

The intention of “Açoquitla” (lines 9–10) and “açoquitlan” (line 12) is aço oc itla, “perhaps something more.”

In line 31, notice the notary don Antonio Valeriano, with the same name as the famous governor of Mexico Tenochtitlan in the late sixteenth century, from Azcapotzalco, and his grandson of same name who was governor of both Azcapotzalco and Tenochtitlan in the early seventeenth.

-----

*Doc. 17 here is a fuller illustration. Another example is in Karttunen and Lockhart, “Textos en náhuatl del siglo XVIII,” Estudios de Cultura Náhuatl, 13 (1978): 153–75. It is true that a very significant infusion of Spanish legal lore had already taken place early in Stage 2, as the corpus of Nahuatl governmental texts from Tlaxcala for example shows very clearly. Yet at that time the point-by-point correspondence with Spanish genres and wording was far less close than later.

----------

Este manuscrito fue publicado por primera vez en Beyond the Codices, eds. Arthur J. O. Anderson, Frances Berdan y James Lockhart (Los Ángeles: Centro Latinoamericano de UCLA, 1976), Doc. 14, 96-97. Sin embargo, la transcripción, traducción, y una nueva introducción se presenta aquí provienen de los documentos personales de Lockhart.

El manuscrito original se encuentra en la Colección de McAfee, Biblioteca de Investigación de la UCLA, Colecciones Especiales.

[Introducción por James Lockhart:]

En 1700, o antes, las organizaciones municipales de muchos de los altépetl del centro de México, especialmente las más grandes, habían absorbido muchos de los conceptos y procedimientos de la ley española que se estaban produciendo documentos legales en los mismos modos que usaron los españoles, arreglando los elementos exactamente en el mismo orden, con equivalentes cercanos de las fórmulas españolas y otro vocabulario. El presente texto es de este tipo. * Sin embargo, este tipo de texto por lo general retiene muchas huellas de los rasgos tradicionales nahuas, y no fueron siempre tan bien informados acerca del español como parecen de ser. El ejemplo aquí es una notificación de errores en el género español, y la frase en español se utiliza realmente como una etiqueta para el texto. Sin embargo, es al revés, se habla de una pena de notificación.

La situación es que el español Andrés González viene disputando sobre ciertas tierras con los habitantes del distrito de San Simón (Pochtlan), la misma entidad que emitió el Doc. 5, el testamento de 1695 de Angelina. Se reconoce ahora que un gran pedazo de 100 quahuitl pertenece a los indígenas, pero el objetivo principal del documento es que no hay de hacer más declaraciones sobre la tierra que ha sido objeto de controversia, y sanciones pesados, de hecho, y probablemente poco realistas, son establecidos como un elemento de disuasión contra cualquiera de ellos tratando de reabrir el asunto.

Andrés González (sin "don" y, probablemente, una persona bastante humilde en el mundo español) no se expresa específicamente como un español, pero se le refiere como español en este contexto por haber sido llamado "señor". Gradualmente, la familia está acumulando terreno en el distrito de San Simón; Andrés es el padre del comprador de la tierra en el Documento 17 de Beyond the Codices, también referente a San Simón, publicado en 1738.

Una característica típica y tradicional de los procedimientos aquí es el papel importante de un grupo anónimo de habitantes del distrito. Aunque se hace referencia en el náhuatl a San Simón como un barrio (línea 3), el grupo asistiendo se llama tlaxilacaleque (línea 4), basado en el término tradicional, tlaxilacalli, distrito constitutivo de una altépetl. Es muy probable que el grupo constaba en su totalidad o en su mayoría de oficiales o dirigentes del distrito, para "tlaxilacaleque" significaba tanto “los habitantes” como “líderes de la entidad.”

Este es el náhuatl de la etapa 3, pero en poca ocasión algo específico de esa etapa. En la línea 9, es posible que la forma extraña de la palabra "niacmo" lleva el préstamo popular del artículo “ni”, tampoco, siendo, de este modo, el equivalente de ni aocmo y significa, “ni tampoco." La o de aocmo, "ya no", se omite en otros lugares en el texto también. Una demostración más completa de los fenómenos de contacto de la época se ve en Doc. 17 y se discute allí.

Uno de los signos principales de la ortografía de etapa 3 es que [z] se convierte en [s]. Aquí, a pesar de la fecha, ese cambio aún no ha sucedido. Sílaba-final más [s] todavía se escribe principalmente [z]. Pero la fusión de [s] y [z] como [s] ha tenido efectivamente lugar, lo que podemos notar por el hecho de que la [s] estándar está generalmente híper corregida a la [Z], por ejemplo, en "coztaz" (línea 17) para "costos". En línea 18 [s] y [z] se invierten, "asotez" de azotes, "latigazos".

Con la avanza de la etapa 3, vemos que cada vez más se añade una [y] adicional al principio de los verbos pretéritos, como aquí en la línea 11, "yoconanque", "se lo llevaron", y en la línea 13, "Yomacoque", "se les dieron.” Tal vez el [y] viene de," ya ", y todavía tiene algo de ese significado. Aquí, la mayoría de los verbos pretéritos tienen sólo la o- estándar.

En la línea 2, la palabra Tecpan, lo que significaba originalmente el palacio del señor o gobernante de una entidad, ahora significa el edificio del gobierno, y el cambio no es muy grande, ya que los palacios tenían funciones públicas y en un sentido pertenecía a toda la entidad. La forma "Audensi" para la audiencia, "tribunal en sesión", es vista muy a menudo; Nahuas tendía a omitir el segundo de los dos vocales finales de un préstamo sustantivo español.

En la línea 16, "tzauhtiyez" es el equivalente de tzauctiyez, “será encerrado."

En la línea 19, una sílaba fue inadvertidamente omitida: la intención de "tiliztli" es "neltiliztli."

La intención de "Açoquitla" (líneas 9-10) y "açoquitlan" (línea 12) es aço oc itla, “tal vez algo más."

En la línea 31, observe el notario don Antonio Valeriano, con el mismo nombre que el famoso gobernador de México, Tenochtitlan de los finales del siglo XVI, de Azcapotzalco, y su nieto del mismo nombre quien fue gobernador de ambos Azcapotzalco y Tenochtitlán temprano en el siglo XVII.

[Una nota de Stephanie Wood:]

* El documento número 17 en Beyond the Codices, tiene una ilustración más completa. Otro ejemplo se encuentra en Karttunen y Lockhart, "Textos en náhuatl del siglo XVIII," Estudios de Cultura Náhuatl, 13 (1978): 153-75. Es cierto que una infusión muy significativa de la tradición jurídica española ya había tenido lugar al principio de la etapa 2, como por ejemplo muestra muy claramente el corpus de textos gubernamentales Náhuatl de Tlaxcala. Sin embargo, en ese momento la correspondencia punto por punto con los géneros y la redacción española fue mucho menos cercana que después.

[Traducción al castellano por Melanie Hyers.]