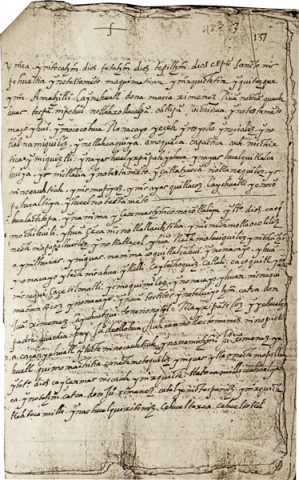

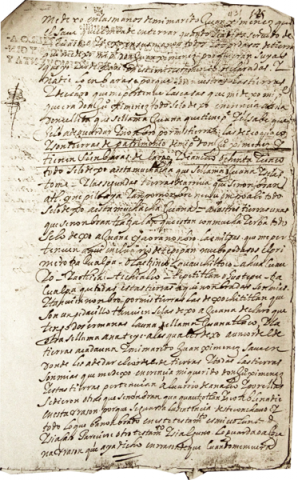

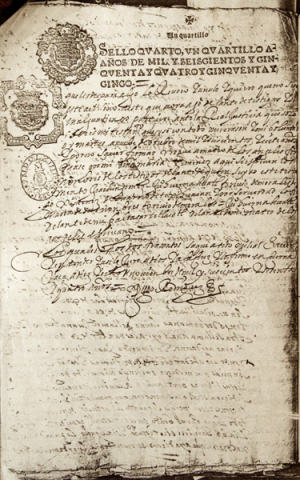

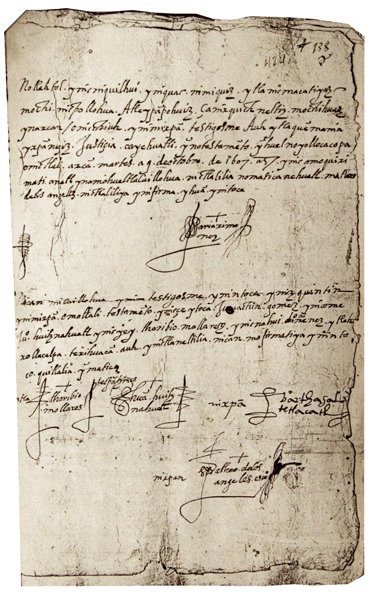

The Testament of doña María Ximénez, Cuernavaca, 1607.

Transcription, translation, and analysis by Robert Haskett.

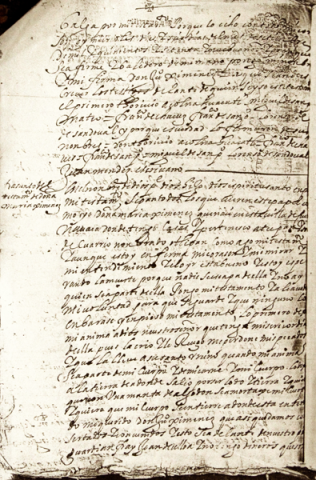

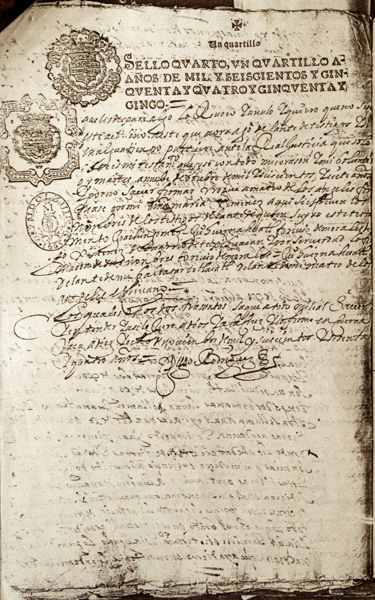

The Nahuatl testament created on behalf of doña María, daughter of the sixteenth-century Nahua lord don Juan Ximénez (whose will also is found in the ENL) have survived thanks to an alleged embezzlement of tribute funds by one of her descendants. In 1694, the long-time gobernador of Cuernavaca, don Antonio de Hinojosa, was held responsible for several thousands pesos worth of the villa’s tribute, leading to the sequestration of his estate. The extensive records of the resulting investigation includes the testament as well as a Spanish translation doña María’s memorial, since it provided proof of the legitimacy of at least some of don Antonio’s property holding; his own claims of indigenous nobility and political power rested on his descent from this noblewoman (as well as her father) on the maternal side.

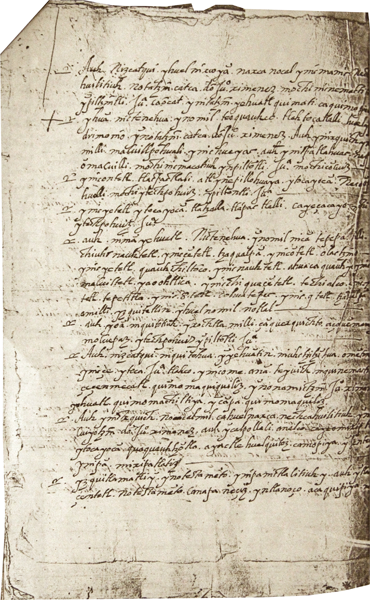

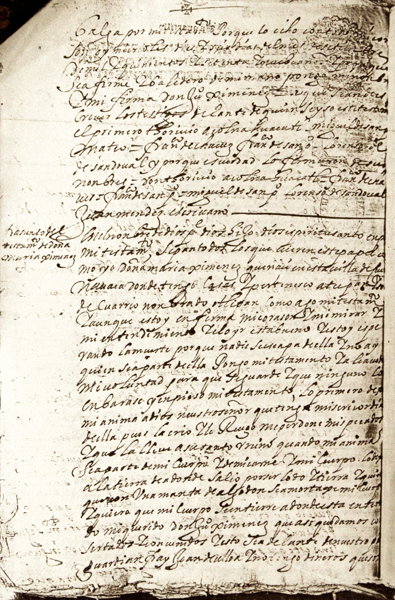

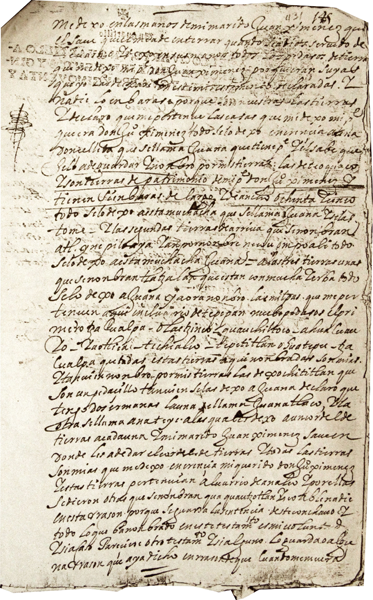

The testament describes an extensive an extensive ancestral estate and presents as well information about familial relationships, the probable effects of epidemic disease, and of course inheritance patterns, making it an excellent ethnohistorical source. Doña María’s will adheres more or less to the genre’s standardized format, most memorably laid out in the model testament of fray Alonso de Molina. She was a consequential figure in Nahua Cuernavaca, the inheritor (after her mother—whose will has not been located--passed away) of the vast majority of her illustrious father don Juan Xinénez’s properties. It was the political and social prominence of the family in the altepetl that attracted the attention of a male Hinojosa, who may have been an upwardly mobile mestizo making his way in the indigenous rather than Spanish world. According to her grandson don Antonio de Hinojosa, “I have some papers which I am presenting to your worship [that include] a testament made by . . . my grandmother doña María Ximénez. In these said papers they left me some houses in which I now live, and lands in different locations.” In fact, most of don Juan Ximénez’s did end up in the hands of doña María, who bequeathed them to her daughter, doña Juana Ximénez, who in the fullness of time married a Hinojosa.

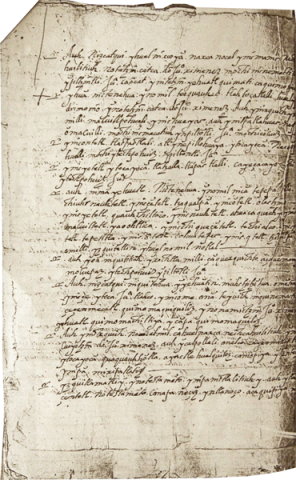

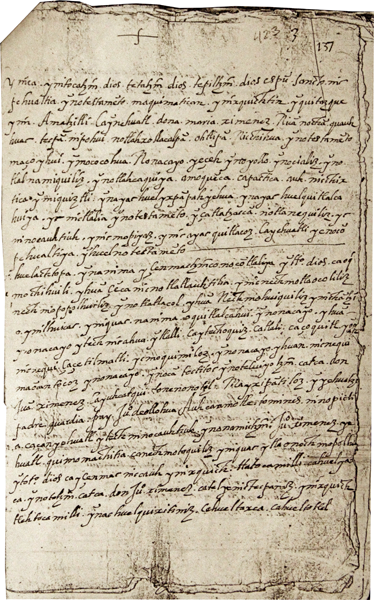

Doña María, whose will was made just about a generation after don Juan’s, was married to a man named Juan Ximénez, a potential point of confusion save for the notary’s scrupulous use of kinship terms to differentiate him from her father. Accordingly, don Juan was called either notatzin (“my precious father”) or, at one point, notecuiyotzin catca (“my late, precious lord”), while Juan (who was never referred to with the lordly title “don”) was nonamic (“my husband/spouse”). Doña María seems to have venerated her late father, to the point that she requested “that my body be buried where my late, precious lord don Juan Ximénez lies buried,” which would mean a high-status internment inside Cuernavaca’s monastery church.

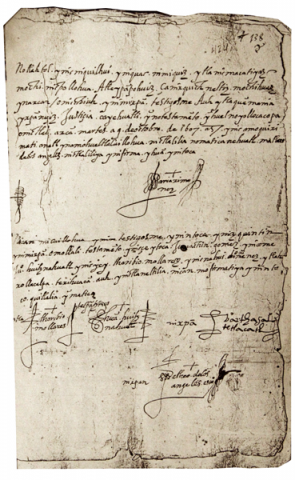

Doña María’s will, drawn up just about a generation after her father’s, is not much different from most other Nahuatl testaments as far as its basic format is concerned; like her father’s, it is written in what James Lockhart has called Stage 2 Nahuatl. It opens with the same kind of formula about life, the inevitability of death, and her burial preferences. And like her father, she had one principal heir, her daughter Juana, though she also left a small amount of property to her two younger sisters. Doña María, who unlike her father could not read or write, relied on the notary to “sign” her name, and on four male witnesses to endorse the veracity of the proceedings. Typically, she or the notary added standard perorations such as the warning that any earlier will of hers would “count as nothing.”

While doña María claimed in this testament to have no money, her extensive properties in the Cuernavaca area included some calpullalli (usufruct property distributed to citizens by district—calpulli—officers) that the family may or may not have been holding properly; the cautious language in the text, which seems to be answering some unvoiced criticism, suggests that there may have been an attempt by the Ximénez to transform it into their own private land. But Doña María actually may not have been too badly off in terms of liquid wealth, since she left the financial part of her dictates to her husband, perhaps trusting that she did not have to spell this kind of thing out for him. The lands still held in 1607 are usually glossed with the terms milli, tlalli, calmilli, one parcel is singled out as an amilli (an irrigated field), and as in her father’s testatment others are described as tlacpactlalli. In doña María’s will the property known as Teoquauhco is classed as tlahtocatlalli (ruler’s land), while the entirety of her landed properties are referred to as yn ixquich tlahtocamilli (“all the ruler’s cultivated fields”), still retaining the status adhering to her father’s station in life.

In contrast to her scrupulous concern for land, doña María’s testament lacks bequests of material or household goods. There is no mention of the pre-contact-style feathered headdresses, shields, and musical instruments featured in her father’s will, so it is impossible to know if doña María still possessed any of these heirlooms, if they had been lost, sold, or destroyed over the years, or if they were specifically “male” possessions she would not have retained. Yet a woman of doña María’s status presumably had clothing, jewelry, a range of household goods, and probably even various kinds of saints’ images. She must have expected her husband to make sure that her daughter and heir Juana would receive these kinds of domestic and personal items.

The Ximénez, a noble indigenous family that seemed to lack legitimate male heirs for three generations, finally found them through marriage to the Hinojosas. While the testaments of these Hinojosa men have yet to be discovered, it is clear that they bequeathed and continued to hold most of the landed properties that had belonged to their Ximénez ancestors in the later sixteenth century and early seventeenth centuries.