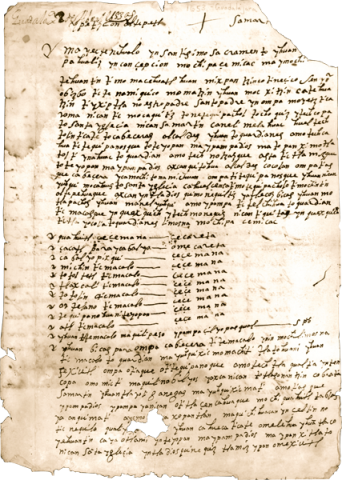

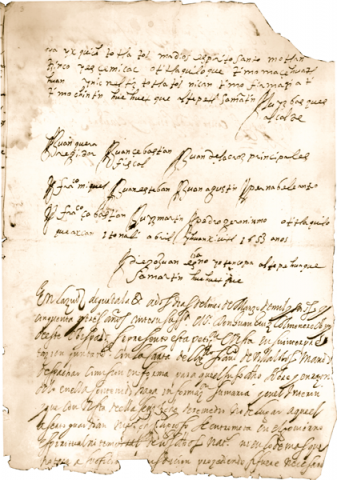

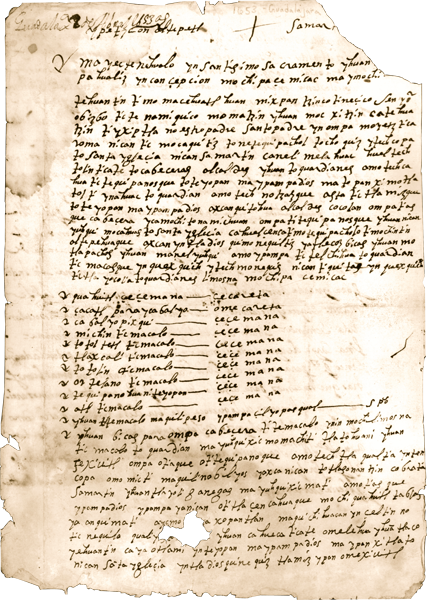

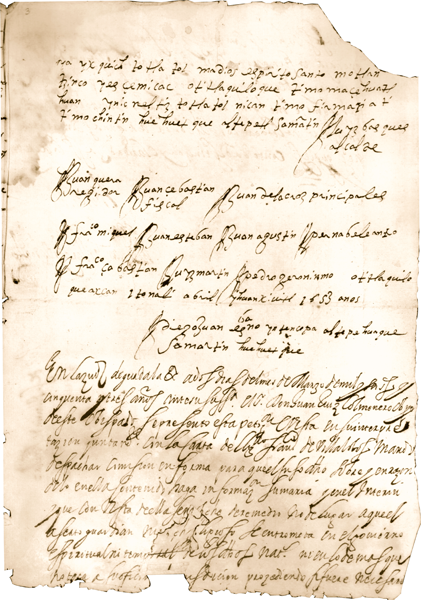

This manuscript was first published in Beyond the Codices, eds. Arthur J.O. Anderson, Frances Berdan, and James Lockhart (Los Angeles: UCLA Latin American Center, 1976), Doc. 28, 174–177. However, the transcription, translation, and a new introduction presented here come from Lockhart's personal papers.

The original manuscript is in the McAfee Collection, Special Collections, UCLA Research Library.

[Introduction by James Lockhart:]

Today the place involved here is known officially as San Martín Hidalgo, some 45 miles southwest of Guadalajara. The cabecera or head town referred to is nearby Cocula. It is likely that San Martín was sub-ordinate to Cocula only for Spanish administrative purposes, but whether it had ever been a part of the altepetl of Cocula or not, the principle of the petition is the same. San Martín’s official structure is not impressive; it sports one alcalde, one regidor, a fiscal of the church, and a notary; all the other members of the petitioning group lack any official position. There is no governor and no one titled don.

San Martín wants independence from Cocula, and as a first and major step toward that goal it requests permission to concentrate on building its own church, not working on that of Cocula. This scenario was seen a hundred times in New Spain, for a large and sightly church was the very symbol of independent status, much as a temple had been in precontact times. We can be sure that the moment San Martín finishes its church, it will start an open campaign for separation from Cocula.

As evidence of their general good faith, responsibility, and trustworthiness, the San Martín people tell how much they do for the Franciscan father guardian (whether in San Martín or in Cocula is not entirely clear). The items and services provided go back to pre-contact precedent, brought up to date by the presence of European phenomena such as horses and candles. Such requirements were virtually universal in New Spain after the conquest.

In its onerous duties for Cocula, San Martín has had to expend resources belonging a local cofradía with a Marian advocation, five steers in fact. This heavy an involvement of a cofradía in altepetl obligations is something characteristic especially of the periphery of New Spain and less seen in the center, where altepetl organization was stronger.

The text belongs to the petition genre along with several others in this collection, and here the Spanish loanword peticion is actually used as a label instead of instead of the common Nahuatl equivalent tlaitlaniliztli. Brief petition formulas make their appearance at the beginning and the end, but the body, like most western Nahuatl and indeed most peripheral Nahuatl, is in very down-to-earth language.

Whether Nahuatl was the first language of the writer and the whole group would be hard to say. In any case, there are many signs that this is peripheral Nahuatl, and some characteristics here belong specifically to the west. Outstanding among the latter is the use of -lo, normally a non-active suffix which precludes the use of a specific object prefix, to indicate the plural of active verbs in the present text, complete with specific objects. Thus “michin ticmacalo,” “we give him fish” (line 28), among many other examples throughout the text. Only two present-tense plural verbs (other than those with progressive auxiliaries) lack this -lo (lines 20, 22).

A hallmark of western Nahuatl also seen in other texts in Beyond the Codices (Documents 8, 27) is the use of the relational word -nahuac, “close to, next to,” indicating indirect objects and taking over some of the functions of -tech, the relational word that was central Nahuatl’s main connector. A classic western-style use in fact occurs here, “ximotlatolti ynahuac toguardian,” “speak to our father,” where -nahuac is “to” or “with.”

In the western Docs. 8 and 27, many preterits of Class 2 verbs are left unreduced, not losing the final vowel as in the center. Here we find in line 43, “otitlacencahuaque,” just that phenomenon; in the center the form would be otitlacencauhque, “we made preparations.” The other preterit verbs in the text, however, are regular by central standards.

Western and peripheral texts in general often show merging in the area of t, tl, and l. Here we see some tl for standard l, as in “timomacehuatlhuan” for timomacehualhuan, “we your subjects” (lines 5, 52) The implication is that some syllable-final [tl] was being pronounced [l]. All other occurrences of t, tl, and l, however, are orthodox.

Peripheral texts from virtually all areas often have an archaic ya for what had become ye in the center. Here we have “ya” for ye, “already,” in lines 43, 47, and 51.

Another general trait of the periphery is the retention of the earlier universal reflexive prefix mo instead of the newer no and to of the center. The text uses mo as we would expect (“timotequipacholo,” “we are concerned,” line 17; “timofirmatia,” “we sign”, line 53).

Texts of the periphery sometimes have qui for cui in many contexts, which happens here in lines 35, 40, 52, and 59, though it must be admitted that the phenomenon is not unheard of in the center either.

The concatenation of language developments called Stage 3 is thought to have formed by around 1640–50 in central Mexico. Our text was written not long after that, and far away from the center. What can we expect in the way of Stage 3 phenomena under these conditions? In general, in recent years we have been finding that the periphery is far more au courant than we might have expected. Here there are no loan verbs, calques, or Spanish kinship terms, but one of the primary diagnostic traits, loan particles, is strongly present. Not only does the text contain two such words, but they are the two words most found in Nahuatl texts from early to late. Hasta occurs in a temporal sense in line 13 with a verb: “asta tictlamizque,” “until we finish it.” Its frequent companion para appears in line 26 as a preposition with a noun complement: “para ycabalyo,” “for his horse.” For a time in the history of research into such matters, the examples here were the earliest known attestations of these two very important words.

But if the text is unmistakably advanced as to loan-words, it betrays a fully Stage 2 situation in respect to pronunciation, as in examples like “bicas” for vigas, “beams” (line 19); “cilyo” for cirio, “candle wax” (line 36); “cobratia” for cofradía (line 41); “lehua” for legua, “league” (line 46); “quera” for Guerra (line 55), or “pernabe” for Bernabé (line 57). The writer also mainly uses c/ç/z instead of s for [s], another Stage 2 trait. We also see here some unanalyzed plurals used as singulars in loan vocabulary, as in “toguardianes,” “our father guardian” (line 22) and “principales,” “leader or nobleman” (line 56). Except in words designating groups or pairs, the plural for the singular in loanwords is mainly a trait of very early texts.

In line 6, “sen ysa” is for cenca ilustrisima, “most illustrious.”

In line 7, “santo padre” is a common unanalyzed phrase for the pope, but “nuestro padre,” “our father,” is rarer and almost gives an impression of code switching. Padre as a loanword generally meant “priest,” like padre in English, and never anyone’s father in any sense.

In lines 16–17, “iuhqui mocahuas tosanta iglecia” is translated as “our holy church will be as if abandoned.” An alternative possibility is “our holy church will be left as it is.”

In line 29, the “totoltetl,” eggs, could have come from either chickens or turkeys, since totolin was often used for both.