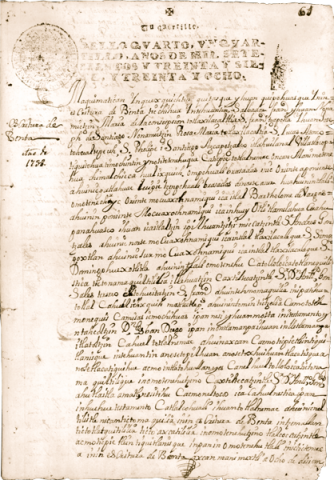

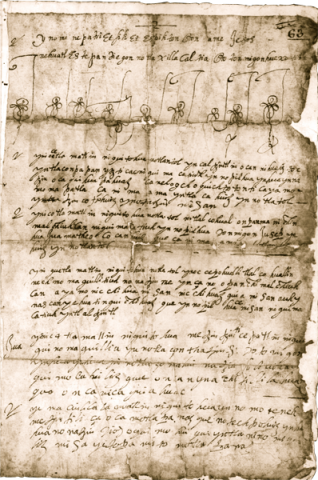

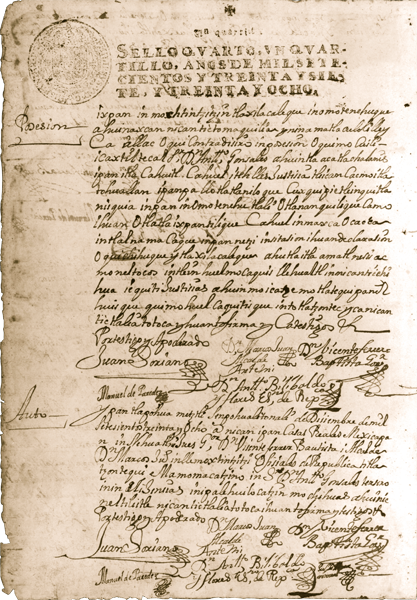

This manuscript was first published in Beyond the Codices, eds. Arthur J.O. Anderson, Frances Berdan, and James Lockhart (Los Angeles: UCLA Latin American Center, 1976), Doc. 17, 100–100. However, the transcription, translation, and a new introduction presented here come from Lockhart's personal papers.

The original is found in the McAfee Collection, UCLA Research Library, Special Collections.

[Introduction by James Lockhart:]

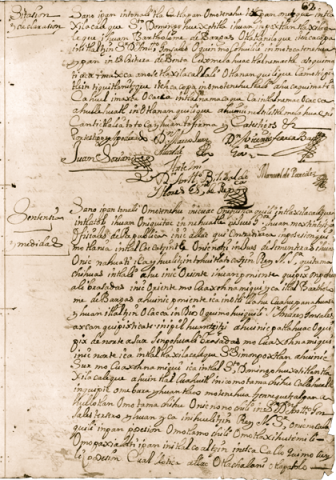

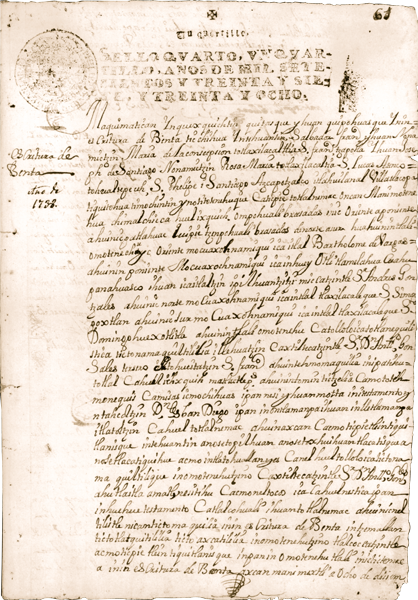

The papers assembled here represent a formidable amount of legal acculturation. A complex protocol of Spanish procedures for land transfer is followed to the letter, and all the relevant terminology is handled either by translations now conventional or by loans, including such a technical loan phrase as amparo de posesión, “affirmation or confirmation of possession.” The same tendencies were seen in Doc. 14, done in the same entity 35 years earlier, but a great advance has taken place. The present writer would never reverse pena and notificación as the notary of 1703 did.

The famous altepetl of Azcapotzalco, not far to the northwest of Mexico City, contained two originally ethnic subdivisions, Mexicapan and Tepanecapan, and the municipality continued to be double (see Gibson, Aztecs, p. 38). The Mexicapan part figures here, and also doubtless in Doc. 14, though it is not specified. In Doc. 14 of 1703, the Mexicapan municipal building was called by the traditional word tecpan; here the Spanish loan phrase casas reales is used.

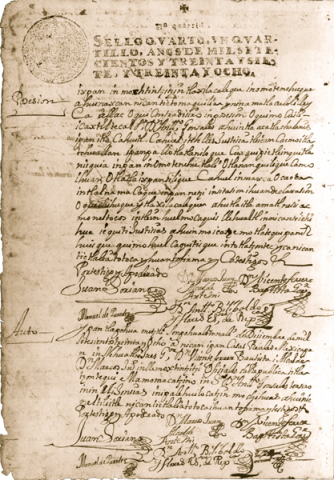

The substance of the transaction is that two indigenous couples are selling to a Spaniard a piece of land that is substantial in size but not of the largest, 40 units by 20, or just double the standard plot size. The price is an unimpressive 10 pesos; not out of line, but one would think it was hardly enough to pay for the elaborate maneuvering and recordkeeping involved here. The money is said to be for masses (for some deceased relative). This far into the eighteenth century, selling land to pay for masses was no longer a very common practice, but the present case proves that it had not died out, at least as a public justification for a sale.

The buyer is the son of the Spaniard who was already accumulating land in the area a generation ago, in Doc. 14. We see the family developing some pretensions. The father was plain Andrés González; the son has acquired the title don as don Antonio González, and he is described as a member of the (Franciscan) Third Order. Since essentially anyone could belong to the Third Order, however, and by this time most solvent Spaniards had the don, we should not be overwhelmed by the family’s rise.

The land is in the same tlaxilacalli where the father of the buyer was active before, Santo Domingo Huexotitlan, though the indigenous owners belong to another district, San Lucas Atenco. Above all, the new purchase borders on land that the father owned and after him his children, so that the González family across two generations is building up a consolidated holding. The piece borders on indigenous holdings in two neighboring tlaxilacalli, but on one side the land already belongs to another Spaniard.

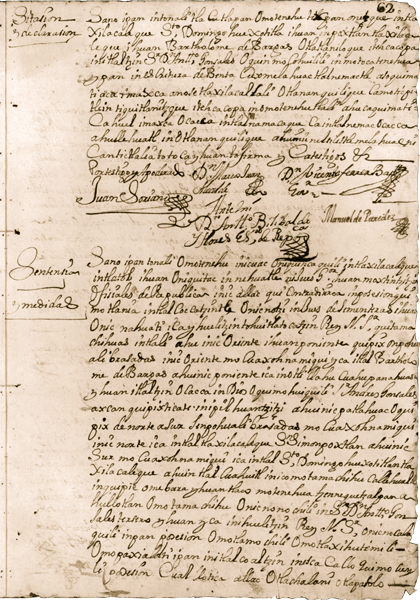

As we have seen, the land is still counted the traditional indigenous way, in 20s. The unit of measurement used, however, seems at first to be Spanish in origin, being called a brazada even in the Nahuatl text. But when it is explained, we see that it is the traditional local unit called the cennequetzalpan, equivalent to a person’s height (no doubt with arms extended above the head), a close relative of the basic indigenous units the quahuitl and the matl. Here it is specified as 21/2 varas (Spanish yards) long.

The text is in a very full-blown Stage 3 Nahuatl. Looking for the most obvious hallmarks, one is surprised to find no clear examples of loan particles, but there is an abundance of the rarer loan verbs. Contradeciroa, “to contradict,” occurs twice (lines 105, 129), and firmaroa, “to sign,” is also there (l. 41). When loan verbs are in the reverential, the causative is most often used, but in this case it is the applicative: “Oquimofirmarhui,” “he signed.” These are technical legal terms, but the most famous loan verb of all was not of that nature of all: pasearoa, often seen as paxialoa, “to stroll or parade about.” Here it occurs (line 122) as “Omopaxialolti,” “he strolled.” This time the more usual causative reverential is used.

But let us return to loan particles. Are there perhaps some after all? We see the word de in the Nahuatl text frequently. But when it is embedded in a long Spanish clause giving the date, that is more code switching than taking a word into Nahuatl. The same with the use of de in unanalyzed loan phrases such as the already mentioned amparo de posesión. But what about the use of Spanish prepositions in describing directions? The text is very far advanced in borrowing Spanish vocabulary in this department. Not only do we find norte and sur, which were frequently borrowed because of the lack of common Nahuatl equivalents, but also oriente and poniente, the solar directions for which most Nahuatl texts stubbornly stick to the traditional phrases. How are we to look at a phrase like “de norte a sur” (line 12), “from north to south?” It is not exactly an unanalyzed phrase, for norte and sur are separate loan-words, and all the elements of such an expression can be moved around and substituted for one another. We could say that de, “of, from,” and a, “to,” are at least on the verge of being loanwords.

An important part of Stage 3 Nahuatl was the use of some native vocabulary as the automatic equivalent of certain Spanish words and expressions. The present text is full of this phenomenon. The most productive word of this type was pia, originally meaning to have custody or charge of, to take care of, even to hold, which in the course of the sixteenth century took on as well the main meaning of Spanish tener, “to have,” and then was used to translate an ever increasing number of Spanish idioms. Here we have pia not only meaning simple possession (lines 9, 112) but to represent “having” a certain number of units of length or width (lines 12, 109, 113, 118), and even (line 28 and elsewhere) not having anything to demand (no tener nada que pedir). The common equivalence of the verb pano with Spanish pasar, “to pass” and related meanings, is also seen here (lines 62, 71).

In Stage 3 Nahuatl the third person singular form of the instrumental relational word ca—ica—came to be the equivalent of Spanish con, “with.” Here we see (line 64 and elsewhere) “yCa testigos,” “with witnesses.” In traditional Nahuatl when two things border both are subjects of the verb, but here we see that one piece of land borders ica, “with,” another (line 110).

Yet the text is by no means an extreme example of Spanish language influence. It retains quite a few conservative elements, for example the use of the old hybrid expression caxtiltecatl for a Spaniard rather than the newer español.

The orthography of the sale proceedings is quite individual. Some of the traits are widely seen in Stage 3 texts, others are unique or rare and not necessarily tied to any particular time. As usual with texts of this time, s has generally replaced c/ç/z, far more consistently than in the Azcapotzalco text from 1703 (Doc. 14). Also as with a good many texts of Stage 3, the old value of ll has ceded to something close to Spanish ll, so that the digraph generally represents [y], earlier written as y. The text has only a single y representing the glide (in “yes,” “it will be,” line 30) ; all the others represent the vowel [i]. Examples of ll for standard y are rife, for example “allac” for standard ayac, “no one” (line 105). As usual in this style, former ll is written single, with “tlali” for tlalli, land,” etc. In fact, in Stage 3 ll was increasingly written single regardless of how [y] was represented.

Also frequently seen in late texts is h for ch; here we see such things as teh- for tech-, “us” (line 23). how this might reflect pronunciation is not clear, but it may have some relation to the weakening of many syllable-final consonants that was becoming acute across the course of the seventeenth and especially eighteenth centuries. Probably related to this phenomenon is the writing of syllable-final -uh as -c, something frequently found in the Toluca Valley of this time, where weakening of final consonants was of epidemic proportions (see Pizzigoni, Testaments of Toluca). An example is “icqui” in line 57 for iuhqui, “like, as.”

All of the above orthographic tendencies are common in Stage 3 texts. The present document contains in addition some unorthodoxies that may be local or personal idiosyncrasies. Where we expect the sound [s] we often find tz, normally the representation of [ts]. Thus in line 12 “tzenpohuali” instead of “cenpohuali,” standard cempohualli, “twenty,” and even “Gontzales” instead of “Gonsales,” González (line 17). On the other hand, tz is never written as s or c. We can suspect the general lenition of [ts] to [s], but the evidence is not clear.

Several times the sequence cui [kwi] appears as cu, [ko], thus in line 77 “cux” for cuix, “perhaps, question word.” In other kinds of Nahuatl this combination of rounded consonant plus vowel has become simple consonant plus rounded vowel, and the same may be true here.

Although unstressed i is usually written standardly, quite a few times it appears as e, especially word-finally, as in “matlactle” for matlactli, “ten” (line 24). The same can occasionally occur in other positions, however, as in “quemotlania,” standard quimotlania, “he requests it,” line 59. One quite frequently sees Spanish unstressed e represented in Nahuatl texts as i; this is a similar merging, but in the opposite direction and with native vocabulary.

While most tl is written standardly, some unorthodoxies with the digraph may point to some kind of merging. Three times we see the combination ltl (lines 5, 118, 137); once tl is in the place of standard t (line 20), and once a final -tl appears as l (line 130).

An idiosyncrasy of the writer that probably bears no relation to pronunciation is that he almost always represents syllable-final [w] as -hu, although in that position [w] is unvoiced in Nahuatl and is conventionally written as -uh, whereas hu is the normal convention for voiced prevocalic [w]. Thus we find for example “ipatihu” (line 23) instead of ipatiuh, “its price."

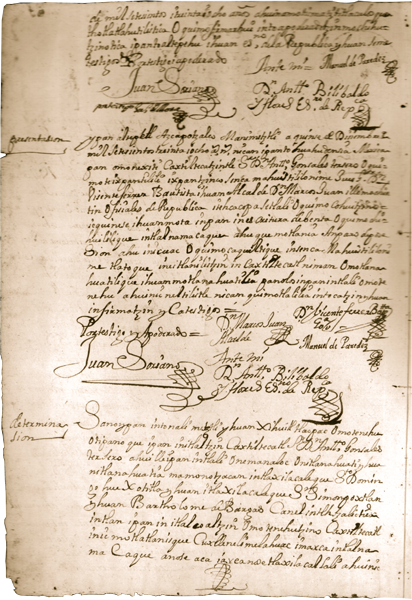

In line 26 the great-grandfather of the sellers, Esteban Diego, in view of the passage of so much time, is given the title don, which in his own testament we see that he did not bear during his lifetime.

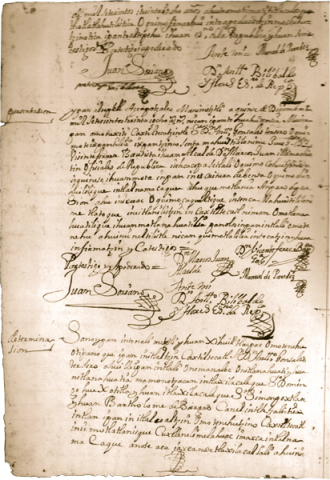

In line 45, the Juan Soriano acting on behalf of the sellers is very possibly the same as the person of that name present in Doc. 5 of 35 years earlier. The name is Spanish in type, though the person may not be.

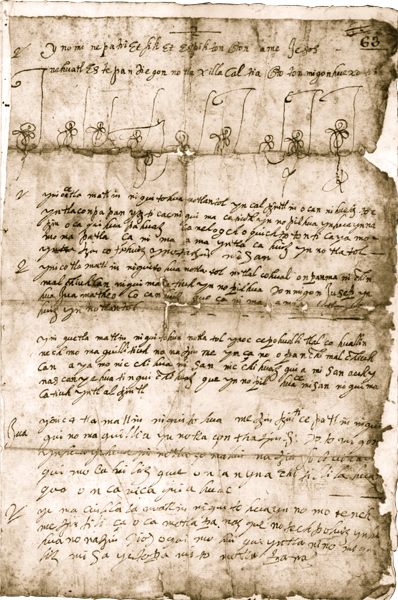

In line 79, the sentence breaks off at the end of a page. This statement doubtless would have continued as at the end of other sections: “[to show] that it is true we put here our names and signatures, with witnesses.”

An entirely different document, the will of the sellers’ great-grandfather referred to the main text in lines 26–27, was pasted onto the last leaf of the record of the proceedings (lines 162–93). The document or fragment is undated, but it shows signs of being from an earlier time, and given the stated relationship between the sellers of 1738 and the testator, one could estimate a date of sometime around 1630 to 1650. No hints of Stage 3 phenomena are seen. Some land, already called purchased land, is referred to as being at Chimalchiuhcan as in the main text, and is left to a descendant. These facts are probably authentic, but they are far from proving that the later sellers had inherited the parcel.

The writing is very individual, hardly that of a well trained notary of any period. One is tempted to speculate that the will was written by Esteban Diego himself, with the last part giving evidence of the extremity of the writer’s condition.

It was not possible to decipher further the partially torn and perhaps garbled section at lines 186–88. Possibly it contains a place name. The letters at the end of this part could also be divided as “nica guiahuac,”, i.e., nican quiyahuac, “here outside the house,” a frequently seen phrase.