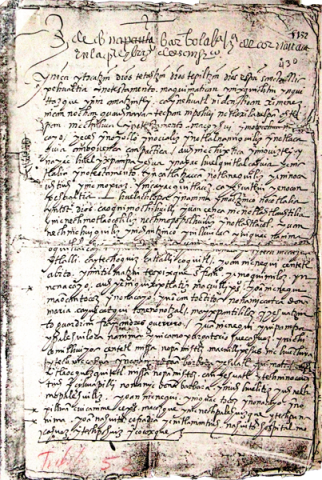

The Testament of don Juan Ximénez, Cuernavaca, 1579.

Transcription, translation, and analysis by Robert Haskett.

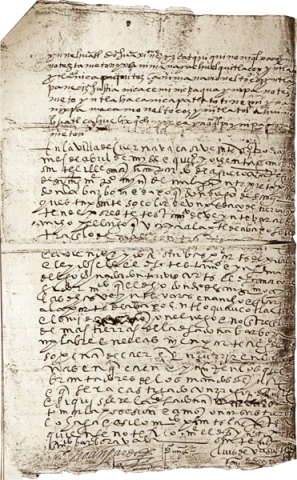

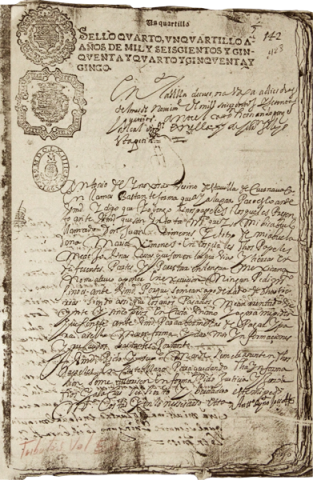

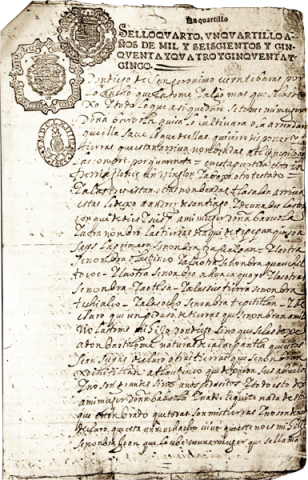

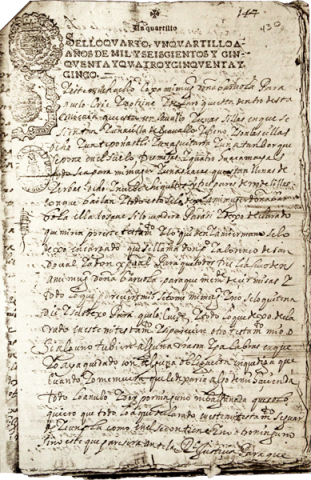

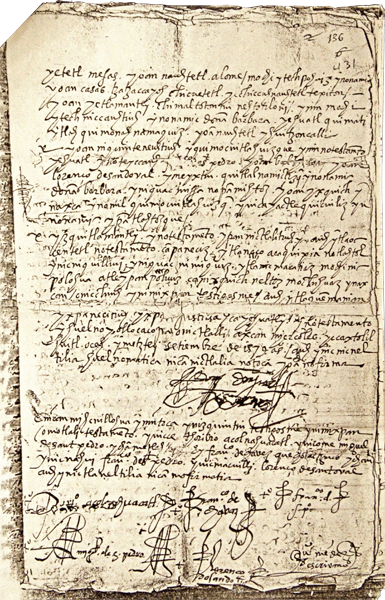

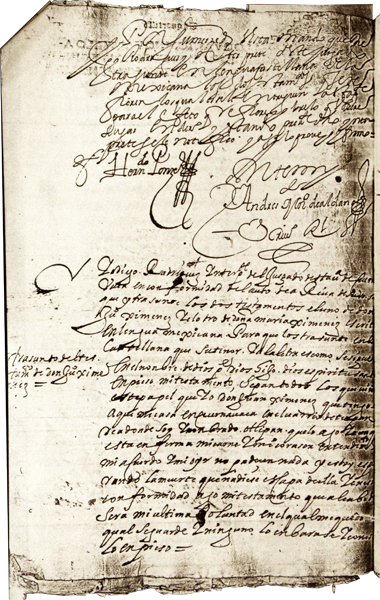

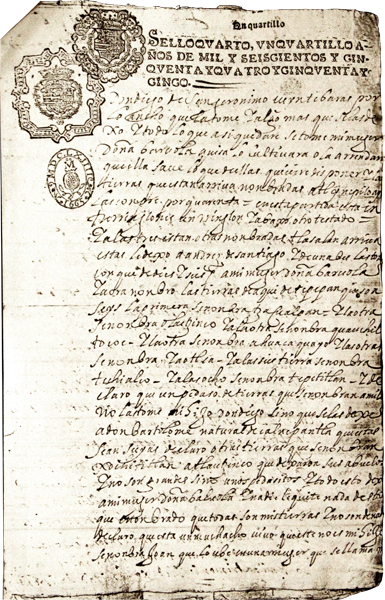

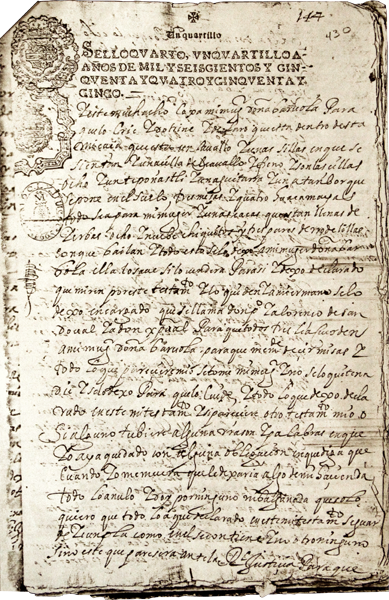

The Nahuatl testament left by the noble don Juan Ximénez is found in records held in Mexico’s Archivo General de la Nación dating from 1694. The litigation covered in them has to do with the sequestration of the goods and properties of don Juan’s descendant, don Antonio de Hinojosa. A long-time gobernador (head of the cabildo, or town council) of Cuernavaca, don Antonio was being held responsible for the payment of several thousand pesos in missing tribute funds, which he had allegedly embezzled. Don Juan’s sixteenth-century will and a later Spanish-language translation of it (written on outdated official stamped paper bearing the slogan “sello qvarto, un qvartillo a años de mil y seiscientos y cinqventa y qvarto y cinqventa y cinco”) were submitted to prove that don Antonio was the legitimate owner of some of the seized lands. The testament describes an extensive array of material goods, property, and familial relationships, making it an excellent ethnohistorical source.

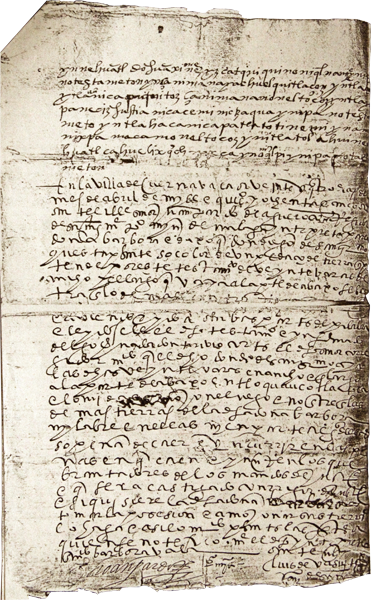

Don Juan’s will adheres more or less to the genre’s standardized format, most memorably laid out in the model testament of fray Alonso de Molina. It reveals the possessions and relationships of a wealthy indigenous lord who has adopted many of the trappings of Spanish culture of his day, yet a man who also retains many cherished items with strong Mesoamerican roots. He was a prominent local leader of an altepetl that, despite having a not insignificant Spanish presence, remained politically a semi-autonomous Nahua community governed by an active and self-conscious indigenous town council. The will makes it clear that don Juan had been married twice, with his second wife and principal heir still living in 1579. The unexplained death of the first wife could well be linked to the outbreaks of epidemic diseases that plagued central Mexico in the sixteenth century, but the testament is mute on this point. Don Juan himself may have died in the great sickness that raged in central Mexico between 1576 and 1581.[1]

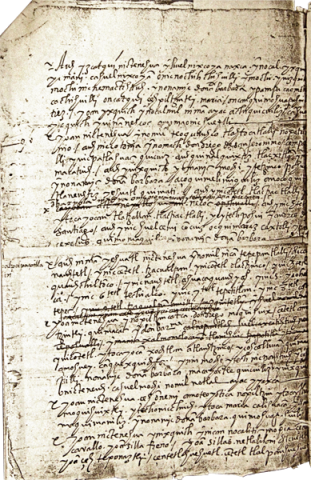

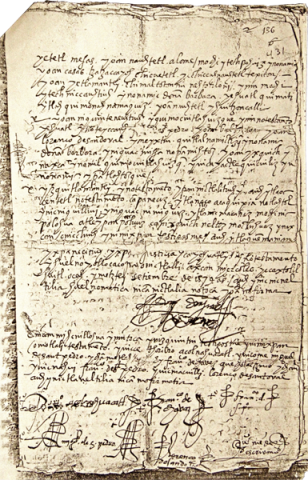

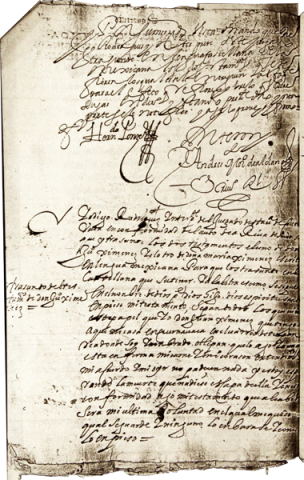

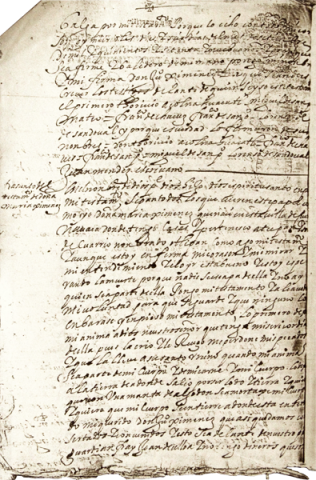

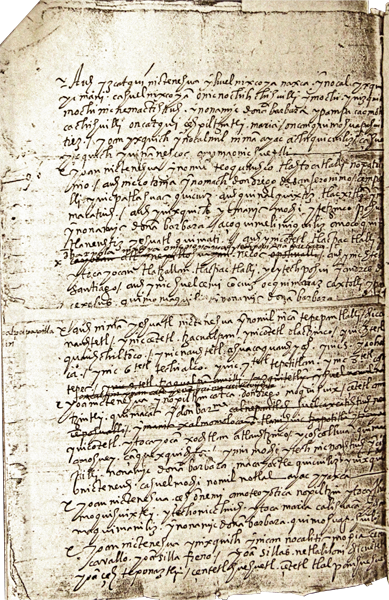

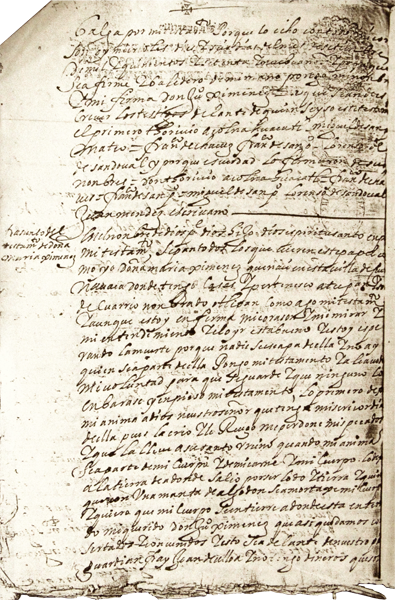

Linguistically, don Juan’s testament is written in what James Lockhart calls Stage 2 Nahuatl, in which loanwords consist primarily of names, other nouns with no ready equivalents in the original language, and the like.[2] It opens with an invocation of the Holy Trinity, assurances that though his body is ill, there is nothing wrong with his mind, and that he is making the testament voluntarily.[3] Also standard are the requests and bequests he makes in terms of his burial and other donations to the church, as well as the format of the balance of the document, where his specific wishes connected with his property and possessions are made. The testament ends with an equally typical identification of his executors (three in this case, including a younger brother named Francisco de San Pedro) and an invocation of witnesses—five men who seem to be prominent indigenous lords—and the attestation of Juan Méndez, the notary who wrote it. The language laying out the duties and responsibilities of these eight people includes similar kinds of “perorations” (admonitions that the testator’s desires are to be upheld or protected in some way) discussed by Caterina Pizzigoni in her study of Nahuatl wills from Toluca.[4] The notary Méndez added some standard language guaranteeing the veracity of this will, that also expressed the generic notarial belief that the presence of the witnesses would insure that “no one at all will be able to violate it [the testament] (ayac huel quitlaçaz).[5]

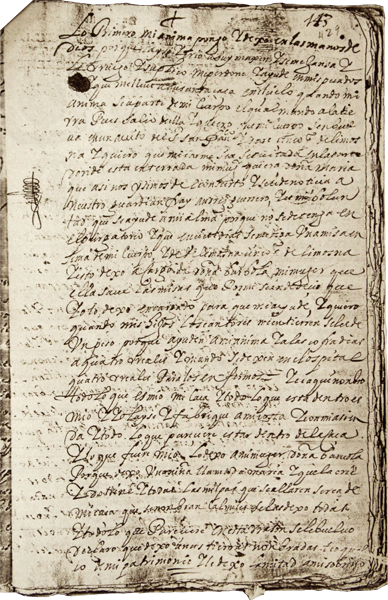

Don Juan wished that his internment would be a pious, Christian one. He told the notary that “I want my body to be wrapped in a habit, a cloak of the friars of Saint Francis” (nicnequi çentetl abito yn intilmatzin teopixque S.t Fran.co yc moquimiloz yn nonacayo), and that it be interned inside the church (probably the church of the Franciscan convento, now Cuernavaca’s cathedral); all of this would suggest long after his death that he had been among the local Nahua great and good.[6] He seems to have been a member of a cofradía, and left some money for the good of his soul in

Purgatory, as well.[7]

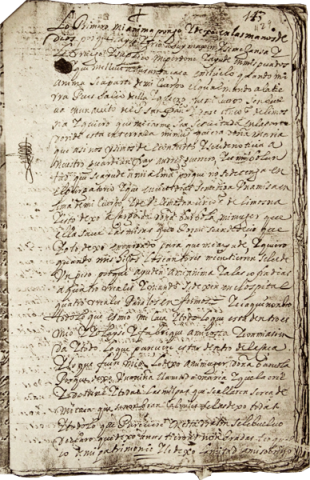

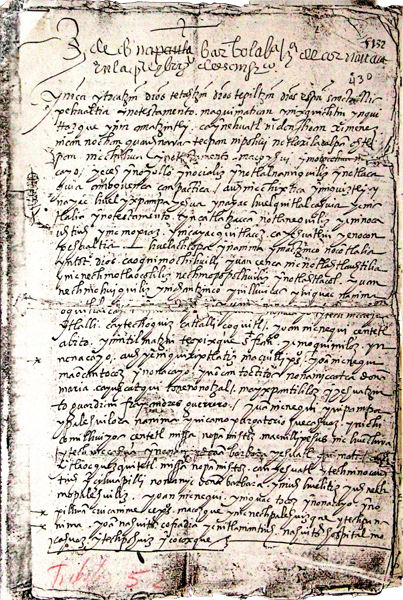

Don Juan’s landed properties include a complex of houses (more properly, a collection of separate rooms and inter-connected buildings that was typical of lordly indigenous dwellings at the time), the house lot (calmilli), and a number of named rural lands that seem to have been scattered geographically around the greater Cuernavaca area; his holdings were referred to collectively by the diaphrase nomil notlal (my cultivated fields, my lands).[8] A marginal note, “noble land [pillalli] in the calpulli [subdivision of the altepetl]” may also refer to all of don Juan’s properties, but possibly just to one or a few specific plots.[9] One of these would be what seems to be don Juan’s most important parcel, a property called Teoquauhco, land that more than a century later remained a key possession for his descendants. This land is described as being “my cultivated field Teoquauhco, [which is] ruler’s land, my patrimony (nomil teoquauhco tlahtocatlalli nopatrimonio). While in pre-contact times tlahtocatlalli may have been altepetl land assigned to rulers (tlatoque) on the basis of their status rather than private property, by the late 1570s don Juan seems to have regarded it as entirely his own possession; it certainly retained this status over the next several generations.[10] Don Juan also held nine distinct plots of land (probably in close proximity, if not contiguously), referring to them collectively as Tepepan tlalli. He also held and bequeathed two amiltzintli, or irrigated fields; in this case the –tzintli suffix may act as a diminuitive rather than an honorific. Finally, don Juan left three plots of land glossed as tlacpactlalli. The seventeenth-century Spanish translation of the will rendered this literally as tierras de arriba (lands above, or “highlands”), and this could be so. The center of Cuernavaca lies at a point between the lower slopes of the mountains separating it from the Valley of Mexico and the lands of its own valley. It is a landscape cut by many ravines, so that parcels located on these slopes or on the elevated areas at the edge of ravines would merit the designation “highlands.” Yet the possibility still exists that the word tlacpactlalli may have had a more specific meaning of some sort that deferentiated it from other kinds of land (highland pasture, perhaps, or land on wooded slopes that was a source of firewood); on balance, it is certainly worth keeping an open mind about this term.

Don Juan’s second wife, doña Barabara, was his principal heir. She benefitted from the persistence of indigenous-style inheritance patterns (in which property was often left to multiple heirs, both male and female); a recurring lack of a legitimate male heir was to confront the Ximénez family over the next two generations, in fact.[11] Don Juan did have an illegitimate son, Juan Moquihuix (amo teoyotica nopiltzin ytoca Jhoan moquihuixtli), but his father left him nothing aside from doña Bárbara, who was assigned the responsibility of looking after the boy’s welfare. The bequests of land in this testament are not without their complications and uncertainties (at least at our remove in time and space). A nephew, don Diego de San Gerónimo, is the only male to receive any kind of landed bequest in the form of a small section of Teoquauhco, yet the statement immediatedly following this bequest—“everything located on [the land] belongs to my wife, doña Bárbara. Perhaps she will cultivate it, or rent it; she will decide”—suggests that don Diego may have received use rights rather than true ownership. A man named Andrés de Santiago, who was apparently renting one of the plots of tlacpactlalli, is given the chance to buy it for sixteen pesos payable to doña Barbara; it is uncertain that he ever did so.[12] Aside from the illusive category of tlacpactlalli, don Juan’s property holding strategies and the pattern of his bequests do not depart in any starkly significant way from well-studied and understood norms associated with Nahuatl testaments written in colonial central Mexico.[13] They confirm the existence of such things in a provincial area near to the Valley of Mexico that has not been well studied in terms of its indigenous-language testaments. Apart from his landholdings, don Juan mainly seems concerned that other kinds of material possessions found in his house—a European table and chairs, saddles, storage boxes of various sizes and designs, some pre-contact-style musical instruments and paraphernalia: drums (teponaztli, huehuetl, and tlalpanhuehuetl), little dancing shields (chimaltotontin nehtotiloni), and feathered headdresses (yhuitzoncalli).

Endnotes:

1.) Cline, Colonial Culhuacan, 13; most of the wills studied by Cline date from the end of this period, 1580-81.

2.)Lockhart, Nahuatl as Written, 114-125; Lockhart, The Nahuas, chapter 7. Aside from basic nouns and names, a few loans typically have forms such as testigosme, in which a plural Spanish work, “witnesses,” receives a second Nahuatl plural suffix, “-me,” and in which the loan noun firma (“signature”) has been transformed into a verb with the addition of the indefinite third-person prefix “mo-“ and the Nahuatl suffix “-tia,” to provide that thing: mofirmatia.

3.) AGN Tributos vol. 52, exp. 17, fols. 430r-432r. A number of scholars have remarked on these standard traits: Anderson, Berdan, and Lockhart, Beyond the Codices, 23-27, provide a groundbreaking summary of the enduring characteristics of Nahuatl testaments; Cline, Colonial Culhuacan, was the first major English-language study of the genre; see also Wood, “Adopted Saints,” 264. Caterina Pizzigoni, Testaments of Toluca, 9, notes that most of these traits are typical of Stage 2 Nahuatl. The opening formula—common on a basic level across the genre regardless of location—was shaped by a model testament included in the 1569 confessional manual of Fray Alonso de Molina; see Cline, “Molina’s Model Testament,” 13-33, and Lockhart, The Nahuas, “Appendix B. Molina’s Model Testament,” 468-476.

4.) Pizzigoni, Testaments of Toluca, 21.

5.) AGN Tributos vol. 52, exp. 17, fol. 431v.

6.) Tributos vol. 52, exp. 17, fol. 430r. Don Juan’s notary may have adopted the loanword habito (habit), but unlike his admittedly somewhat later counterparts in Toluca did not use any Spanish loanword meaning “shroud,” who on the other hand eventually abandoned “habit” and replaced it with the Nahuatl –tlaquentzin (“one’s garment, garb”); Pizzigoni, Testaments of Toluca, 15-16. A burial in an advantaged position inside a church was most often attainable by only the most prominent of Nahua citizens (even if other, more humble people made similar requests). See Wood, “Adopted Saints,” 269; Cline, Colonial Culhuacan, 24; Pizzigoni, Testaments of Toluca, 16-17; based on the study of her own extensive group of testaments, Pizzigoni concludes that this kind of request to be buried near a spouse was comparatively rare. An analysis of a similarly large body of wills from Cuernavaca obviously would be necessary to determine if don Juan’s request is similarly unusual for his time and place.

7.) For a discussion of similar bequests, see Pizzigoni, Testaments of Toluca, 17-18; the author notes that mentions of cofradías and requests to them for help in mass, burial, etc., are very rare in her sample.

8.) For a recent discussion of houses, house lots, and other properties see Pizzigoni, Testatments of Toluca, 22-25. For instance, the author notes that in that region through the later seventeenth century were complexes of separate structures, each of which might be used by a nuclear family, arranged around a patio.” [22] Rather than calmilli, the majority of the Tolucan wills used the term ihuicallo tlalli (“’the land going with (the house)’.”

9.) Cline, Colonial Culhuacan, 141, defines pillalli as “private lands of the nobility.”

10.) Ibid; Cline believed that in that late-sixteenth-century altepetl the term tlatocatlalli continued to refer to lands attached to the office of the ruler, rather than to private properties held by him.

11.) This kind of inheritance pattern can be discerned in the testaments collected in Anderson, Berdan, and Lockhart in their pathbreaking Beyond the Codices, 44-79.

12.) AGN Tributos vol. 52, exp. 17, fol. 430v.

13.) For excellent discussions of these topics see Cline, Colonial Culhuacan, 59-85; Pizzigoni, Testaments of Toluca, 11-13, 27, and Kellogg and Restall, “Introduction,” 2-4. For instance, following Pizzigonio, while at least in Toluca it was not usual for a wife to be her husband’s principal heir, “the testator generally preferring blood kin of the following generation,” doña Barbara may have received the land with the kind of understanding identified by this author that “she will hand it on to the children later” [20-21], which in fact she did.